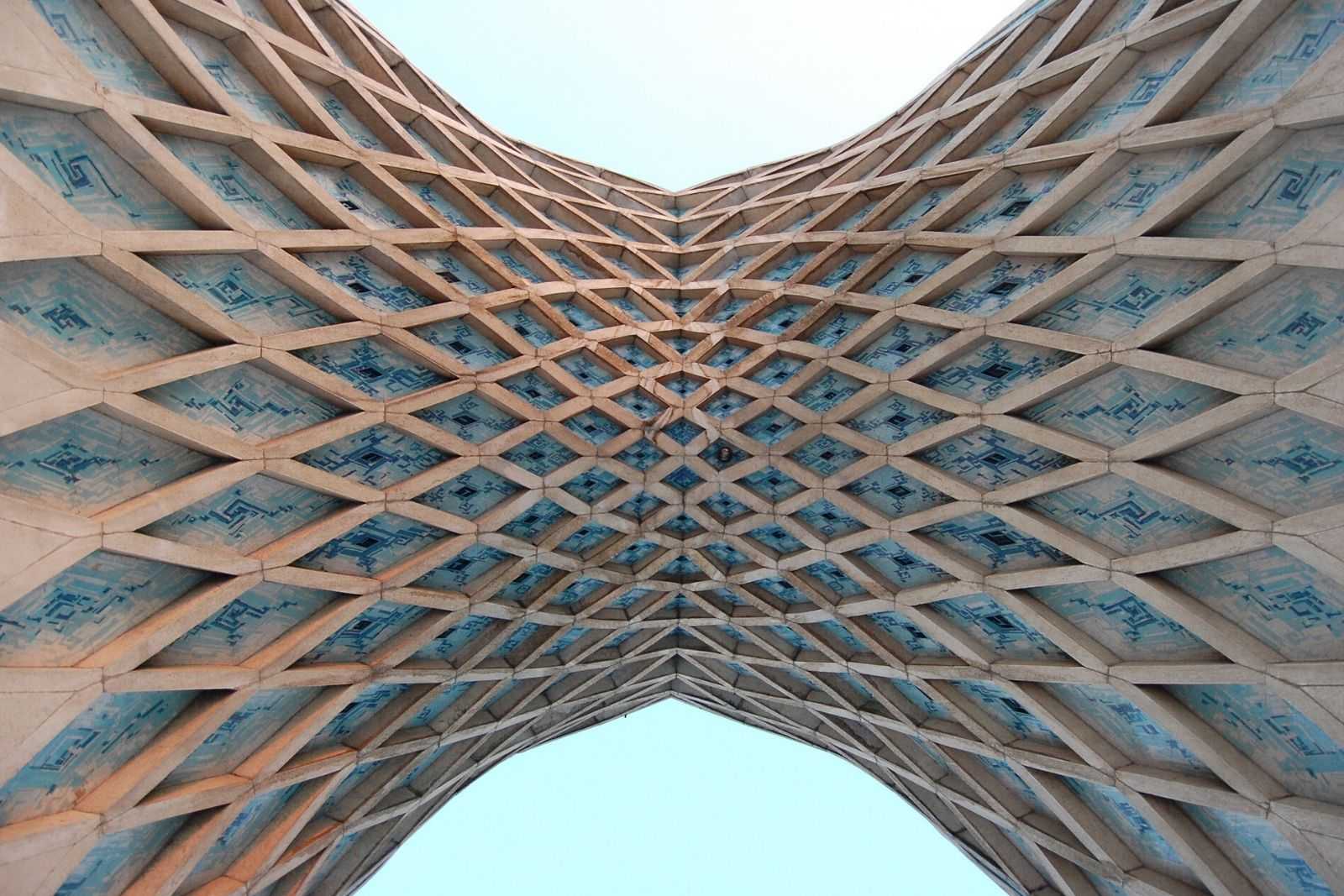

Few literatures can pride themselves in such a masterpiece as the Shahname or ‘Book of Kings’ of Ferdowsi. Despite being written about a thousand years ago, it is still widely and deeply appreciated by lovers of epic literature, and especially Iranians. Their very identity has been shaped by this book.

It tells the reader the mythical and glorious history of the Iranian kings up to the Arab conquest of Iran in the mid-seventh century AD. However, it should rather be viewed as a collection of stories about love and wisdom, piety and faithfulness, tyranny and pride, divine retribution and destiny.

The Shahname is not just a book about the glorious kings and heroes of old. It is a religious, historical and cultural tapestry, in which different layers of the ancient and medieval Iranian culture are interwoven. The material incorporated in the Book of Kings by Ferdowsi, who was using much older written and oral sources while compiling his book, reaches all the way back to Proto-Iranian and even Proto-Indo-European times. They contain references from the ancient religion of Iran: Zoroastrianism and its mythology.

Thus, the Shahname is a wealthy repository of pre-Islamic Iranian lore, as well as an epic work of epic volume, which has preserved the tales of ancient Iran for us.

The Shahname is a book worth reading for everyone, and lucky is the one who can enjoy it in the original Classical Persian. Nevertheless, even without knowing it, you can find it translated into a number of languages.

However, there are things you need to know before going out to find the right version of the book. In this post, we will discuss some crucial aspects of the Shahname.

Here are 7 important/interesting things you might need to know about the Shahname.

1. The name of the author of the Shahname

Abu al-Qasem Ferdowsi Tousi - this is the name traditionally given to the author of the voluminous epic history of the Persian kings. However, as strange as this may sound, this is not his personal name. In fact, we are not sure about what his real name is at all.

Abu al-Qasem is the kunya (patronymic) of this person, meaning ‘the father of al-Qasem’. Ferdowsi is his takhallos (check here for the etymology of the word ferdous-paradise), i.e.his poetic name (‘of Paradise’) and Tous is the name of his native city.

Various sources give different names for Ferdowsi.

Nonetheless, it is considered that the most reliable source in this case is the author of the 13th-century Arabic prose translation of the Shahname, Fath ibn Ali Bundari Isfahani. This is the full name of Ferdowsi given by him: Al-Amir al-Hakim abu al-Qasim Mansur ibn al-Hasan al-Firdawsi al-Tusi.

Ferdowsi was born in the Iranian province of Khorasan, in one of the surrounding villages of Tus.

The year of his birth is now accepted to be 940 AD. No exact date can be given for the year of his death, though it probably occurred sometime after 1010 AD, when he is supposed to have finished his book.

2. The language of the Shahname

As we know, the Book of Kings is written in Early New Persian. If you are not familiar with the history of the Persian language and the periods of its development, you are welcome to check this article regarding the historical development of Persian.

Thus, the language of Ferdowsi is more archaic than modern Persian. It not only contains ‘outdated’ expressions and archaic cultural terms, but also a huge number of (one might say) ‘pure’ Persian and Iranian words, which are no longer in use.

Arabic words, which by the time of Ferdowsi himself had massively penetrated into Persian, are not seen as often in the Shahname as in other works of the same period. It has been estimated that only 2% of the words in the Shahname are of Arabic origin, although this number might go even lower if we take out all the passages added later (while in later texts the percentage of the Arabic words could reach as high as 60-70%).

A number of reasons can be provided to explain this phenomenon. However, two seem to be the most relevant ones:

1. The nature of the sources used by Ferdowsi. The Book of Kings of Ferdowsi is based upon the lost prose Shahname of Abu Mansur, completed in 957 AD. This version of the Book of Kings was based on a number of sources, many of them dating back to the Sasanian period when Persian was free from the influence of Arabic.

2. The personal choice of Ferdowsi, based upon his taste, as well as his cultural and national preferences. Ferdowsi could have used many Arabic synonyms familiar to his reader, but overall he preferred to use ‘pure’ Persian words instead of Arabic ones. Some researchers and many Iranian readers consider this to be overt opposition to the overwhelming dominance of elements of the Arabic culture and language over the Iranian one in that period.

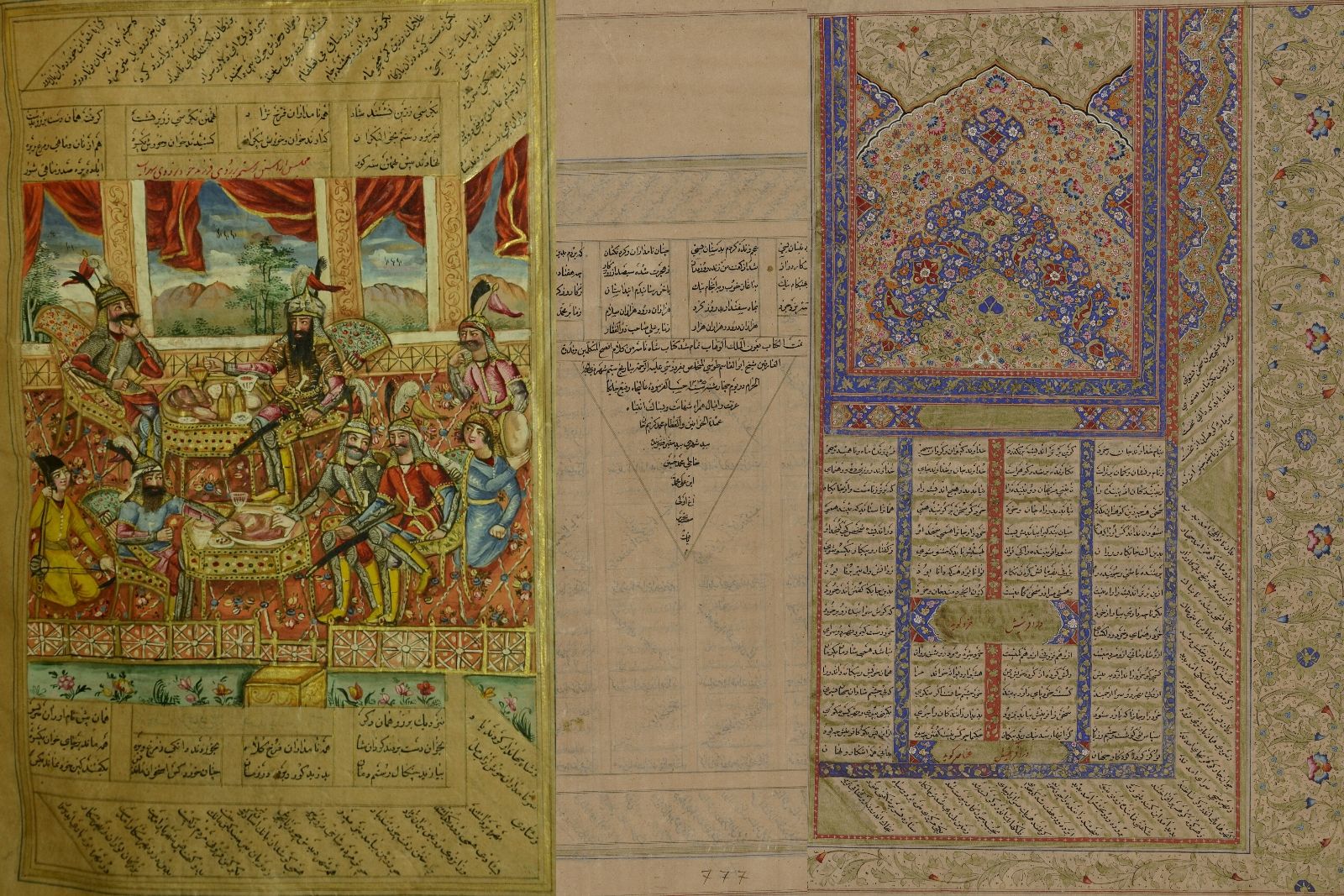

3. The oldest known manuscript of the Shahname

The Shahname was completed around 1010 AD, i.e. more than a thousand years ago. However, as unfortunate as it is, we do not possess the original manuscript of the Book of Kings. Instead, we have hundreds and hundreds of Mss of varying quality and volume dating up to the 19th century.

However, the oldest known manuscript of the Shahname dates back to 1217 AD, i.e. two hundred years after the completion of the original. It is kept in the National Central Library in Florence, Italy. It was discovered in 1978 by the Italian Angelo Piemontese and is generally known as the Florence manuscript (of Shahname). Here you can have a look at the digitized version of the book.

However, the Florence Ms does not include the Shahname text in its entirety. It begins with Ferdowsi’s Introduction and the reign of Gayumath (the first king) and ends with the reign of Key-Khosrow, one of the most famous and prominent kings in the Shahname.

The date of the completion of the Ms may be found at the end.

4. Two main editions of the Shahname

Today, there are a handful of editions, old and new, good and bad, of Ferdowsi’s Shahname.

Their publication started in the early 19th century. A number of distinguished scholars and lovers of Persian literature, such as the Englishman Turner Macan, the Frenchmen (of German origin) Jules Mohl, the Germans Vullers and Landauer, all pioneers in this field, dedicated much of their time to collecting and collating various Mss, in order to have a version as close to the original as possible.

The reason why all these scholars tried to accomplish this painstaking work, was because they (and us) did not have the original manuscript written by Ferdowsi himself.

Over time, many mistakes crept into the text, as various scribes tried to reproduce the Book of Kings. Words that were not familiar to the scribes got replaced by more familiar ones, verses and passages were added, some were edited out entirely and so on.

There are two main editions of the original text of the Shahname, which are respectively known as the Moscow edition and Khaleghi-Motlagh edition.

Moscow edition’s text, as appears from its name, was prepared and edited in Moscow in the 1960s and early 70s by a number of distinguished scholars (Y. E. Bertels, I. S. Braginskiy, B. G. Gafurov, A. Nushin, A. Y. Bertels, M.-N. O. Osmanov, etc.) at the Academy of Sciences of USSR.

It is based on the 1275 AD manuscript of the entire Shahname (called the London Ms), which is kept in the British Library, London. It is interesting to note that even though at that time (before the discovery of the Florence Ms) it was mistakenly considered the oldest Ms of the Shahname in existence, it continues to be the oldest complete Ms of the Shahname.

This is quite a trustworthy and useful edition, despite not using the Florence Ms for obvious reasons.

The entire set consists of 9 volumes.

Khaleghi-Motlagh edition, now extensively used by many scholars and readers, is the new edition of the entire Shahname text, prepared by Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh (Hamburg). Its 1st edition consists of 8 volumes which have been published between 1988 and 2008. It has a number of advantages over the former edition, the foremost being that it utilizes a number of new manuscripts unknown to the editors of the Moscow edition. It is also quite reader-friendly, for the editor has made extensive use of punctuation marks and vowel signs.

5. The translations of the Shahname

It is not such a big deal if you do not know or cannot read Persian (especially Classical Persian). Numerous translations of the Book of Kings have come into existence. It has been translated, fully or partially, into several languages.

However, as I do not have information about all the possible translations of this book into all those languages, I will confine myself to talking about the most familiar languages and the best translations that I know of.

English translations of the Shahname:

1. The Shahnama of Firdausi, translated by A. G. Warner and E. Warner in 8 volumes (London, 1905-1923). This is the only complete translation (in verse) of the book in English. It uses many archaic words, but it goes well with the overall spirit of the book.

2. Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, translated by Dick Davis (Viking Penguin, 2006). This is a prose translation which incorporates most of the Shahname, but is not a complete translation. Short passages translated in verse can also be found in this text. Reviewers have generally expressed positive opinions on the language and accuracy of this translation.

French translations:

1. Le Livre des Rois par Abou’lkasim Firdousi, translated by Jules Mohl. This is the complete prose translation of the text into French.

2. Shâhnâmeh: Le Livre des Rois, Introduction and translation by Pierre Lecoq, Preface by Nahal Tajahood, Paris, les Belles Lettres, 2019, 1740 p.

German Translation:

1. Firdosi's Königsbuch (Schahname), übersetzt von Friedrich Rückert. Aus dem Nachlaß hrsg. von E. A. Bayer, Berlin, 1890, 1895, 1896 (in three volumes).

This is a partial but very nice translation by the famous German poet F. Rückert.

Russian Translation:

The most complete and aesthetically pleasing Russian translation of the Shahname is the six-volume translation by Ts. B. Banu-Lahuti et al. (1957-1989):

1. Фирдоуси, Шахнаме. Том 1-ый, От начала поэмы до сказания о Сохрабе. Издание подготовили Ц. Б. Бану-Лахути, А. Лахути, А. А. Стариков. 2-ое издание исправленное. Научно-издательский центр “Ладомир”- “Наука”. Москва, 1993.

6. The heroes of the Shahname

Despite its name, the Book of Kings, the Shahname tells the reader or the listener the stories of the glorious heroes of pre-Islamic Iran. That is why it is called an ‘epic’. There are hundreds of ‘pahlawans’ (heroes) who fight for their honor and the glory of their kings. Which ones are the most popular in the Shahname and why?

Rustam, son of Zal is definitely the most central and popular character of the Shahname, especially its mythical first half. He is a native of Sistan, a prosperous region back then on the banks of Helmand (in modern-day Iran and Afghanistan), which in early historical times was populated by Scythians warrior tribes (from around the 2nd c. BC).

He is most certainly the beloved character of Ferdowsi, although, like all humans, he is not devoid of human vices. However, his most outstanding virtues are his superhuman strength, courage, humility, cunning, and last but not least, his not so much philosophical but rather practical wisdom.

Rustam, who is of heroic lineage himself, figures in a number of stories, which relate the story of his seven labours on his way to free Kay Kawus, his other journey to free Kay Kawus from the hands of the king of Yemen, his battle with his son Sohrab, which has a quite tragic outcome, his battles with Kamus of Kushan, the emperor of China, the demon Akwan, etc. In all of these stories he always has an opportunity to show his outstanding strength. However, he never loses his piety and ascribes his accomplishments to the goodwill of Yazdan (= God).

Isfandyar, the son of the king Goshtasp, the crown-prince of Iran, is not less praised in the Shahname. Admittedly, he has a much shorter lifespan than Rustam. However, in many of his characteristics he still very much resembles the latter.

Many of his adventures are similar to that of Rustam, most striking of which is the story of his seven labours on his way to Ruyin-dezh to free his two sister-wives.

His life ends in a tragic duel with Rustam, who shoots a fatal tamarisk arrow into his eye. This story, entitled the “The story of Rustam and Isfandyar”, exposes the core difference between these two characters. While both of them show the most eminent virtues of a true hero, that is they have superhuman strength and pious humility, one of them finds the disobedience to the royal authority as an unheard-of crime, the other is very much the master of his own, and chooses whom to serve and whom not. The first one is the crown-prince Isfandyar, who is ordered by his father to chain and bring Rustam to the court, while the second is Rustam.

Bizhan, son of Giv, is the representative of the incessant and stubborn youth, who is splendidly gifted with the most prized virtues of youth, valour and courage. He rushes into battle (like in the story of Davazdah Rokh), he responds to the king’s invitation to go and fight against wild boars, and he recklessly goes to the border of Turan to see the beautiful daughter of Afrasyab, the despotic ruler of Turan.

There are numerous other interesting and lively characters portrayed by Ferdowsi in his book, like the old and wise Gudarz, the arrogant Tus, the innocent and straightforward Siyawash, Bahram Gur, the unrelenting hedonist, the beautiful and brave Gordafarid, and many others.

It is one of the greatest virtues of Ferdowsi, alongside his exquisite talent of composing an almost ideal type of verse, that he is able to portray these different human characters, all lively and human.

7. The role of religion in the Shahname

The Book of Kings was written in a period when Islam, one of the most popular world religions, was at the height of its cultural and political influence. Indeed, the Caliphate was no longer that mighty superpower it was 200 years prior, but various Islamic rulers with their states were exercising their power from Cordova up to the borders of India and Chinese Turkestan. It was the Golden Age of Islamicate culture, destined to end amidst the destruction and savage wars brought by Turkic and Mongol warlords.

Yet, if we read the Shahname, one thing comes to our attention in particular. Ferdowsi is not much of a devoted Muslim. The subject he chose for his book alone is enough to convince us of that. However, it would be a stretch to say that Ferdowsi is an apostate.

Two things strike us in the Shahname. One is his complete display of pious humility in front of God, which according to him is the most important virtue of his beloved hero Rustam himself.

The other one is his fatalism. Everything is predestined and decided upon. We are all just pawns of the cruel and unpredictable universe, which plays chess with our suffering souls. It would be amazing to observe how the same kind of philosophy pervaded the ancient stories of the Iliad and Odyssey, composed a bit less than 2000 years ago before the Shahname, in a drastically different environment and society.

The overall indifference of Ferdowsi towards any particular religion and especially any kind of religious dogma is well testified in the fictional story of Alexander of Rome (i.e. of Macedon).

In one of the scenes, when Kayd, a fictional Indian king, wants to interpret his dreams, there comes a dream where four people are pictured, and each of them tries to pull the linen they all hold in their hands towards themselves. The explanation that is given for this dream is fascinating. Those four are the founders of four world religions of those days: Christianity, Islam, Zoroastrianism, and Judaism. Despite the fact that basically three of these four are highly revered in Islam as prophets, none of them is in any manner distinguished or praised. Most strikingly, this is true also in the case of the founder of Islam, the prophet Muhammed, who is not distinguished from the rest of the company any special title or blessing.

I think this shows the universality of the religious outlook of Ferdowsi himself. Despite being obliged, as a token of formality, to briefly praise the Prophet in his introduction, this passage comes to show the devotion of the author of the Shahname to the God of the universe, irrespective of religious dogma.

Or, to put it simply, Ferdowsi was not a very religious person.

Online resources for studying the Shahname

The Persian text of the Shahname in Ganjoor (Moscow edition).

Collection of online introductory articles on the Shahname in www.heritageinstitute.com.

The English translation of the Shahname (online) available on www.heritageinstitute.com.

A Short Introduction to the Persian Metre (عروض ʿarūż) – part 1, part 2, part 3. By Iskandar Ding.

Images from the illustrated manuscript of the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp. On Metropolitan Museum’s website.

More illustrated pages from the manuscripts of the Shahname. On MacGill Library website.

Radio Shahname. 30-minute introductory talks (in Persian) on the contents of the Shahname.