Everything has a beginning and an end. A 19th-century American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who was also the first American to translate the “Divine Comedy” into English, once wrote: “Great is the art of beginning, but greater is the art of ending.” This is particularly true about leave-taking. In social interaction, greetings mark the beginning of the process, while leave-taking formulas indicate the rational end of a conversation. Unbelievable as it may seem, the “ritual” of leave-taking in Persian is considerably a more sophisticated social act than that of greeting, as it involves numerous phases and sub-phases of encounter and interaction. Here, for the sake of brevity, we will restrict ourselves to mentioning only some of them since it would take a whole volume to list all the subphases and expressions with proper etymological discussion. Thus we decided to pick up the expressions that follow these criteria:

Those that are conversation-terminating expressions primarily used in the last or pre-last phases of leave-taking.

Collocations that are widely used among speakers.

Expressions that are culturally significant.

We have also tentatively categorized them into two classes: simple and complex or combined. Under the complex class, all the combined formulas are listed without further exploring the subjects of etymology and social contexts.

Simple Formulas

خدا حافظ [xodā hāfez] / خدافظ [xodāfez] / خدافس [xodāfes]

Meaning: “Goodbye”, lit. “may God protect you.”

Social Context: There is one foolproof reason we began our discussion with this expression: You can use it across the full range of contexts and situations, both formal and informal. Furthermore, in some special social situations, when you are not in the mood and your anger is a little bit out of control, xodāfez will be the only utterance to be brought into play to end the unpleasant conversation.

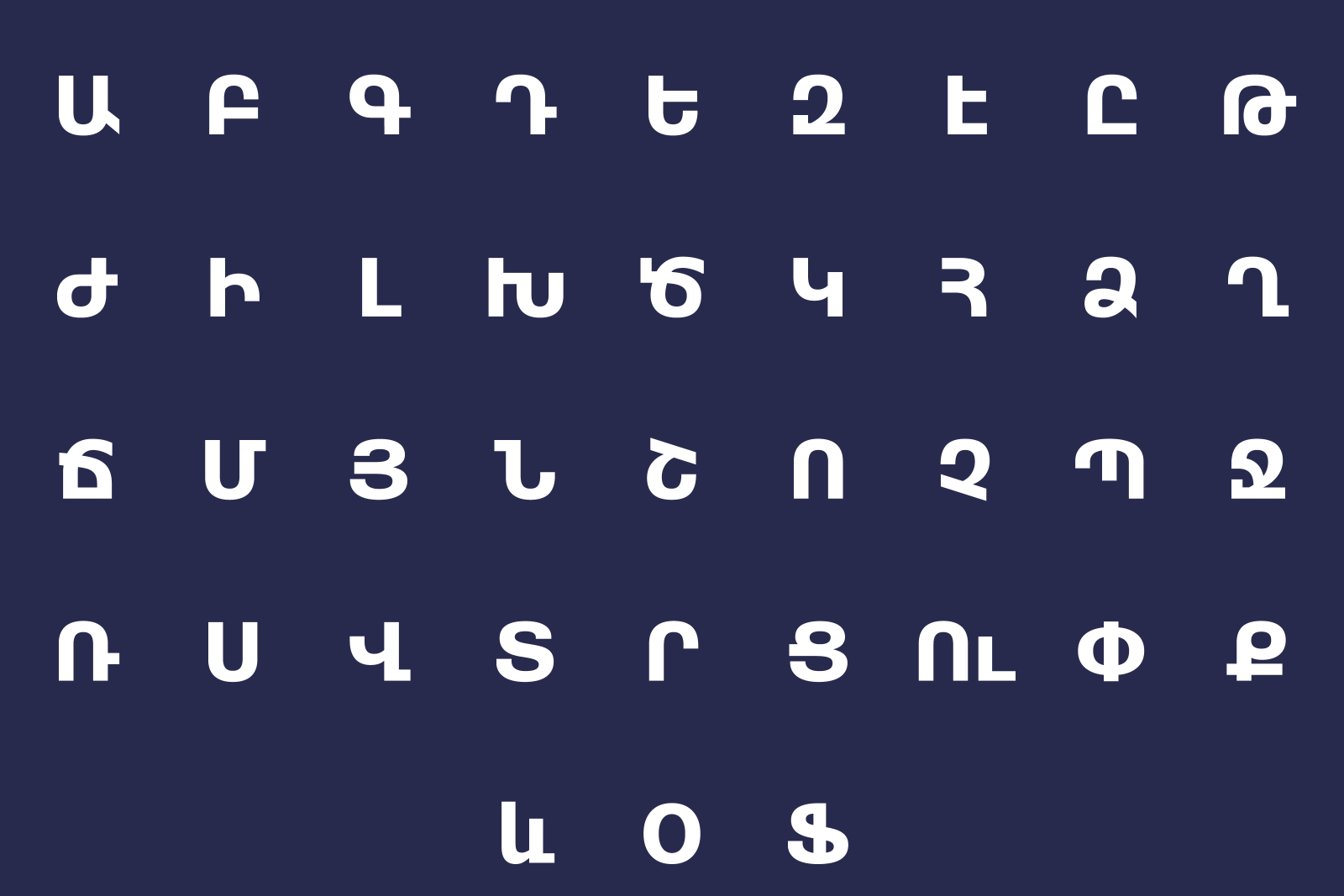

Etymology: This form came about as a result of clipping of the expression خدا حافظ [Xodā hāfez] which ultimately goes back to the more elongated خدا حافظ شما باش [xodā hāfez-e šomā bāše (< bāšad)], literally meaning “may the god be your protector.” Typologically, we can find a few examples of clipped forms of God-bound expressions in other languages worldwide, c.f. English goodbye < God be with ye (probably influenced by the formations like good-day, good evening, etc.), Russian spasíbo < Old East Slavic *sŭpasi bogŭ, “God save (you),” Armenian tghorma (dialectal/“broken” form) “prayer beads” < teroghormya, lit. “may God have mercy on you”. etc. As to the etymological origin of the composite parts, it’s safe to state that the word hāfez “protector” is the active participle (I form) of the triconsonantal root ḥ-f-ẓ, that in essence, covers two core though not unrelated meanings: “to preserve, to protect, to defend” and “to retain in one’s memory, remember, know by heart” (the word ḥāfiẓ, which is used for a person who knows the Koran by heart, stems from this particular meaning).

From the historical and diachronic point of view, things are getting complicated when we touch on the topic of xodā since, in ancient and early medieval Iran, it was never used to denote the meaning of “God” independently. To make things more clear let’s take a look at another word in Persian: it is xod “own, self,” that shares the same origins with xodā < Middle Persian xwadāy “lord, ruler,” presumably from *xva-tāvaya- “one who rules by himself” (Eilers) which could represent an Iranian rendering of the Greek term αὐτοκράτωρ, autokrátōr, c.f. English autocrat (as suggested by A. Meillet, the other reconstructed forms that have been proposed so far are *hvata-āda- “one who sets the beginning of himself” (Hübschmann), *xvatō-dāta- “self-creating” (Bartholomae), *hvata-āya- “self-existing” (Mayrhofer), see Hasandust M. (2014), An Etymological dictionary of the Persian language, Vol. 2, Tehran, p. 1109-1110). The terms for “God” that are well documented in the Old and Middle Iranian languages (and thus were widely used among the ordinary people and the Zoroastrian clergy) are baga and yazata. Supposedly the need for a new word such as xwadāy emerged on the one hand as a result of the Islamization of Iran after the Muslim conquest to substitute the formerly known words for “God”, since they had a strong Zoroastrian connotation, and on the other hand, it can be viewed as an indirect influence from Christianity, as in texts written in Manichean Middle Persian both Māni and Jesus are referred to as xwadāy, or Yišō xwadāy can correspond to Syriac māryā yesūc mšīḥā “Lord Jesus Christ” in the Syriac translation of the New Testament.

(for a more detailed discussion, see Shayegan R.M. The Evolution Of The Concept Of “Xwadāy” “God”: Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Vol. 51, No. 1/2 (1998))

خدا نگهدار [Xodā negahdār]

Meaning: “May God keep you”

Social Context: Xodā negahdār is a more formal version of xodāfez which is not usually used when addressing family members, friends, and companions. The level of politeness and formality as compared to xodāfez somewhat resembles the relationship of dorud to salām (see the discussion here) as besides being more formal stylistically, both xodā negahdār and dorud belong to the more prestige layer of the vocabulary.

Etymology: Contrary to xodāfez, here we are dealing with a pure Persian formation. Having briefly discussed the etymology of xodā, let’s touch on the form negahdār. It is an agent noun made up of two parts: negah, a variant of negāh “look, glance, watch, care” that has undergone a vowel reduction (-ā- > -a-), and the Present stem of the verb dāštan “to have, to hold,” namely dār-, compare the following two variants of the same compound verb “to hold, watch over”: نگه داشتن [negah dāštan]/ نگاه داشتن [negāh dāštan]. The word negāh itself goes back to the Old Iranian *ni-kāϑa, ultimately from the PIE *kʷeḱ-, showing the phonetical development of –ϑ- > -h- word-medially, typical of the Southwestern branch of Iranian languages as opposed to the forms with [s] that are well documented in the subbranch of Iranian languages that are conventionally referred to as “Median” or Northwestern Iranian, but here as a matter of convenience, we will call them “non-southwestern Iranian” since as demonstrated by the following examples the forms with [s] are preserved in the languages that are spoken in the Eastern part of the Iranian language boundary, c.f. Young Avestan ākasa- “to look (at),” Paṣ̌tō ngos “look,” Parthian < ng’h> “look” (probably a southwestern borrowing), < “gs> “clear, evident,” Middle Persian nikāh (note that conventionally it used to be written with -s- (nk’s) in the Pahlavi script).

فعلاً fe’lan [fe:lan]

Meaning: “For the moment”, “bye for now”, “See You.”

Social Context: Are you sure you will see each other again in a few hours or even sooner? Then it is preferred to use fe’lan instead of xodāfez or even combine the two expressions and say fe:lan xodāfez “goodbye for now,” which not only means you are going to meet again but also tells your addressee about your willingness to return and desire for future reunion, even if you don’t have any real intention to see that person again. Thus this formula slightly adds to the hearer’s appreciation and friendliness.

Etymology: < Arabic فِعْلًا [fiʕlan], adverbial accusative form of the triconsonantal root f-ʕ-l, meaning “to do, to act,” c.f. Hebrew פָּעַל [pa'ál] “to do.” Generally, fe’lan is an adverb used to indicate that the action or the narrative event occurs at the time of speaking. However, fe’lan marginally differs from the other adverbs denoting the moment of speaking, namely حالا [hālā], اکنون [aknun], الان [al-ʔān], etc., in that it implies a longer duration of time stretching into the future. Therefore, the given example is correct if it is represented as a direct speech:

بهرام چوبین در نامه خود به پادشاه نوشت فعلا قلعه دارا فعلا در پناه سپاه ایران است

Bahram Čubin dar nāme-ye xod be pādešāh nevešt: “Fe’lan dež-e Dārā dar panāh-e sepāh-e Irān ast!”.

“Bahram Chubin wrote in his letter addressed to the King: At the moment, the stronghold of Dara is under the control of Iran’s army!.”

Thus, using fe’lan would be impossible if the sentence was structured as an indirect speech with a subordinate clause.

می بینمت [mibinamet]

Meaning: “See you (around),” “see you soon,” “catch you later.”

Social context: mibinamet carries on nearly the same function as fe’lan; thus, most of the time, they can be used interchangeably. The main difference between these two is the more informal character of mibinamet; unlike fe’lan, it can never be used in formal situations and when addressing strangers.

Etymology: It is a 1st person Present Indicative form of the verb didan “to look” + 2nd person possessive determiner -et (colloquial/vernacular form, the literary form is -at). It is easy to see that the Infinitive form didan is not the same as its Present Stem bin. That is because in Persian when constructing the Past/ Present finite forms of some verbs, the so-called suppletive forms are used, e.g., bud- (Past)/ hast- (Pres.) “to be,” āmad- (Past) / āy- (Pres.) “to come” etc. With that in mind, let us now consider the origins of the root bin- separately (for didan see the next entry):

bin- (Present Stem) < Middle Persian vēn- < Old Persian vaina-, from Indo-european *ṷei-, c.f. Avestan vaēna-, Sanskrit vénati “he/she sees” etc.

In his famous Naqš-e Rostam inscription written in Old Persian cuneiform, Darius I proclaims the following:

Auramazdā yaϑā avaina imām būmim yaudatīm pasāvadim manā frābara (DNa33-34)

“When Ahuramazda saw this earth, that it was disturbed, then he gave it to me.”

به امید دیدار [be omid-e didār]

Meaning: “Hope to see you again”

Social Context: Functionally, this expression is similar to fe’lan/ mibinamet and differs from them by the level of formality and a relatively low frequency of use. Without any doubt, it is not the phrase you will use when leaving your close friends or relatives; instead, it might be helpful when addressing someone you meet for the first time.

Etymology: the structure of the phrase is

be (Prep.) + omid (N.) + e (Ezafe) + didār (N.)

Let’s then dive into the etymology of the words omid and didār.

omid “hope” < Old Ir. *ava-mati-, from *mati- “thought” (Skt. matí), c.f. Middle Persian ummēd (<’ wmyt’>), also compare ēmēd (<’ dmyt’>) < *abi-mati- (Nyberg H.S. (1974) A Manual of Pahlavi, Vol.2: Otto Harrassowitz, p. 144). In Wiktionary, we came across the reconstructed form *hamwátiš (through labial assimilation and loss of initial h-), an exciting proposal to be further investigated, which comes from the root *ṷat “to believe,” c.f. Parthian hmwd-. However, one must note that except for Armenian hawat and Southern Kurdish himêd/ humêd, none of the hypothetical descendants have the initial h-, and the forms attested in Armenian, and some of the dialects of Kurdish can possibly be viewed as secondary developments.

didār (Noun) <= Past stem did- + suffix -ār, a formation analogous to raftār “behavior,” koštār “massacre,” etc. The form didār is attested already in Middle Persian and ultimately goes back to the form *dītāram, from the Past participle of the verb di- < *daiH, c.f. Young Avestan diδāiti “he sees,” Old Persian dīdiy “Look!” etc.

به امید خدا [be omid-e xodā]

Meaning: lit. “Our hope on God,” “We rely on God.”

Social Context: A god-bound expression used quite rarely and predominantly in formal situations. It is generally utilized when responding to farewells. The other equivalent expressions used in similar contexts are Dar panāh-e xodā / dar panāh-e haq, “Under the protection of God”, dast-e haq be hamrāhet “may the hand of God accompany you”.

Etymology: We are omitting the etymological survey because all the expression constituents have already been discussed.

به سلامت [be salāmat]

Meaning: “Go in peace,” lit. “with health, with safety”

Social Context: Likewise, be salāmat is a formal type of response to farewells which is generally used in formal situations.

Etymology: < Arabic سَلَامَة [salāma], a verbal noun of the form I verb salima, a formation from the root s-l-m (we have discussed it at greater length here). The Arabic feminine ending -at (written with tāʾ marbuṭa) was realized in Persian as -at or -a. It is generally agreed that the words with more abstract meanings tend to be realized with -at. Interestingly, suppose you say this word to an Arabic speaker. In that case, he or she will recognize it as a non-existent plural form of salāma “good health.”

بدرود [bedrud]

Meaning: “Farewell”, “adieu”, “valediction”.

Social Context: Being a word of Iranian origin, bedrud is usually perceived as an element of “Prestige language” that people use to underline their preference for using “pure” Persian words, and the correlation between bedrud and xodāfes, in some instances, resembles one between dorud and salām.

Etymology: probably comes from Middle Persian pad drōd, c.f. Parthian pd drwd [pad drōd] (< OIr.*pati drvatāt-), similar to pagāh “early morning” and padid “visible” is thought to be a Middle Persian neologism (see H. Hübschmann (1895). Persische Studien, p. 42). Also, compare the alternative form (or a double form in case the assumption below is valid) پدرود [pedrud]. It should be pointed out that bedrud is commonly thought to be a form deriving from the combination of be (preposition of direction “to”) and dorud; however, examples from Classical Persian poetry speak in favor of the reconstruction from the preposition pad “on, at, into”.

با اجازه [bā ejāze]

Meaning: “If you would allow me (to leave),” “with your permission.”

Social Context: This expression appears to be the shortening of the opening leave-taking formula با اجازه بنده از حضورتون مرخص بشم [bā ejāze bande az hozuretun morxas bešam] that people say mainly in formal situations when preparing to leave. However, by “cutting off the tail,” it has also significantly lost its formality. It thus can be used in various social situations, even when leaving the company of close friends. Nonetheless, it can hardly be used for family members, one exception being the bizarre situation when let’s say, someone had a little tiff with a senior family member and being unable to channel anxiety “in the most constructive way,” decided to leave by asking for the addressee’s permission. This particular case shows that the alienation caused by disagreements and conflicts might add to the formality of verbal communication.

Etymology: < Arabic إِجَازَة (‘ijāza) “permission, approval,” from the triconsonantal root j-w-z.

مراقب باش [morāγeb bāš]

Inf.: مراقب خودت باش [morāγeb-e xodet bāš] “Take care (of yourself)!”

Form.: مراقب خودتون باشید [morāγeb-e xodetun bāšid] “Take care!”

Social Context: It would not be an exaggeration to say that here we have an expression precisely equivalent to English, “Take care,” which is used not only among close friends but also between strangers. However, in Persian, the two variations cited above show

Etymology: < Arabic مُرَاقِب [murāqib], “controlled,” a Passive Participle form from the triconsonantal root r-q-b,

تا بعد [tā ba:d]

Meaning: “Until later.”

Social context: tā ba:d is exceptionally an informal type of leave-taking, used by the young generation in everyday speech. Functionally it stands on the same line with fe:lan and mibinamet, hinting that the persons involved in the conversation will meet each other again.

Etymology: tā (Prep.) “until” + ba:d (Adv.) “then, after”

tā < Middle Persian tā (Aram. OD), probably from OIr. *tāvat, c.f. Sanskrit tāvat “so large or distant,” Kurm. Kurdish da ku “so that.”

ba:d < Arabic بعد [ba’d], from the triconsonantal root b-ʕ-d, related to the notion of “distance.”

ما رفتیم [mā raftim]

Meaning: “I’m leaving now,” lit. “We left”

Social context: mā raftim is a colloquial expression used only in informal situations that denotes the interlocutor’s intention to leave right at the moment of the conversation. The main feature that makes it sound somewhat like a colloquialism is that the speaker uses mā “we,” but man “I” is meant. This phenomenon is known in various languages, including English; for instance, it can be used when someone wants to speak on behalf of other people or pass the buck of responsibility to the whole group. In Persian, however, it can possibly mean that speaker attempts to affect greater importance to his/ her own personality in a joking manner.

Etymology: mā (1st pers. plural Pron.) + raftim (Preterite 1st. Plural of the verb “to go”).

mā < Middle Persian mā < OIr. *ahmākam, put in Genitive case, compare the Old Persian Nominative vayam.

raftim, Past stem raft- < *rav-ta < *rab-ta, from the PIE verb rebh-” to move.”

روز خوبی داشته باشید [ruz-e xubi dāšte bāšid]

Meaning: “Have a good day”!

Social Context: This expression can be comfortably used in the same contexts where its English equivalent is used.

Etymology: ruz (N.)-e (Ezafe) xubi (N. + Indefinite marker) dāšte bāšid (V. Combound Subjunctive 2nd. Pers. pl. of the verb dāštan “to have”).

ruz “day” (for the etymological discussion, see here)

xub “good” < Oir. *hu-apah-, c.f. Sanskrit sv- ápas- “doing good work.”

شب بخیر [šab be-xeyr]

Meaning: “Good night”

Social Context: In the context of leave-taking formulas, šab be-xeyr is precisely equivalent to English “Good night.” Its use is not restricted by the measure of formality or social situation, and time is the only variable to put any limits on its use. Thus it’s quite obvious that you can say šab be-xeyr either when bidding farewell at night or when going to sleep.

Etymology: We have already commented on the etymological origins of this unit here.

بای بای [bāy- bāy] or simply بای [bāy]

Meaning: “Bye-bye”, “goodbye”

Social Context: Doesn’t that sound familiar? Of course, it’s not hard to guess that Persian borrowed this one from English. To put it briefly, its usage is limited to informal situations, mainly among the youth; thus, one can comfortably say bāy- bāy when saying goodbye to his/ her friends, classmates, companions, etc., but it’s better to avoid using it when leaving the company of people from an older generation.

Etymology: < English bye, Eng. [ɑɪ] diphthong is realized directly as [āy], here is another curious example ساید بای ساید [sāyd-bāy-sāyd] < English side-by-side refrigerators.

The number of Anglicisms in Persian has risen significantly over the last few decades, mainly due to the mass media, internet, and pop culture, to name but a few. On top of that, there is a tendency among the Persian-speaking population to use foreign words instead of words of Iranian origin in everyday speech. This phenomenon has a strong “magnetic effect.” Especially susceptible to it is the younger generation who has developed its own sociolect. For example, among the Iranian youth, you may often come up with someone who will say tāym nadāram “I’m short of time,” using the word “time” instead of traditional vaqt/ vağt (< Arabic).

یا علی [yā ‘Alī]

Meaning: “O, Ali”. The interjection yā is equivalent to English “O” and Ali, in total, Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib is the name of Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law who is considered to be the first Imam and Muhammad’s legitimate successor in Shiite theology.

Social Context: Being a foreigner, you can overleap this one, as we are mentioning it for the sake of knowledge only. The reason is that, au fond, it has a strictly religious connotation, and its use is limited to the adherents of the Shiite religious view. However, in daily usage, it has lost its literal meaning and can be used regardless of religious affiliation. Having said that, it is also important to note that Iranian Sunnis will not use this expression when talking to Shiites for apparent reasons. Apart from leave-taking, yā ‘Ali functions as a standard formula used by Iranians in various social situations, e.g., when standing up, making deals, getting engaged in a collective activity (usually physical labor), and so on. In such cases, historically, it can also be viewed as a shortening of the یا علی مدد [yā ‘Ali madad] “may Ali help us”, an expression that is also widely used in Persian calligraphy.

The other leave-taking formula that is associated with the name of Ali is دست علی به همراحت [dast-e ‘Alī be hamrāhet] “may the hand of Ali guide you” which can be used when bidding farewell to the person who is leaving.

مرحمت زیاد [marhamat ziyād]

Meaning: “May Your kindness be multiplied.”

Social context: marhamat ziyād is another formal way of leave-taking, originally used in prayers, that has acquired the function of a leave-taking formula over time. It is a highly old-fashioned way to respond to leave-taking and is mainly utilized by the older generation.

Etymology: Probably an abridged variant of مرحمت عالی زیاد [marhamat ‘āli ziyād] “May your mercy be graciously multiplied.

marhamat < Arabic مَرْحَمَة [marḥama] “mercy”, verbal noun of the form I verb raḥima from the triconsonantal root r-ḥ-m, encompassing the notion of mercy, also c.f. Hebrew רחם [raḥam], Akkadian rēmum, meaning both “womb” and “mercy, compassion”, Assyrian re’āmu (Black, Jeremy, George, Andrew and Postgate, Nicholas, eds. (1999) A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz, p. 302).

ziyād “many, much” < زِيَادَة [ziyāda] “increase, addition” (Noun), verbal noun of zāda “to increase, to add”. When entering Persian, a group of nouns was realized as adjectives, and ziyād is one of the examples.

به خدا سپردمتون [be xodā sepordametun]

Meaning: “I leave you to God’s mercy”

Social Context: This type of greeting can reasonably be ascribed to the archaic layer of vocabulary. Aside from being a god-bound expression, its level of formality is relatively high, and you will never hear people from the younger generation say this.

Etymology: be (Prep.) xodā (N.) sepordam-etun (Pret. 1st. sing. + 2nd. plural Personal Suffix. -etun )

Past Stem sepord- “to hand over, entrust” < Old Ir. *upa-spṛta, c.f. Skt. spṛnóti “he releases,” Middle Persian abespurtan “commit, entrust,” etc. There is a homonymic verb sepordan, meaning “to trample, tread,” which goes back to the form *spṛta- “to spurn, reject, kick,” c.f. Skt. sphuráti “to spurn”, YAv. spar- “to spurn” (sparōit̰ Abl. sing. (Vyt 35)), Middle Persian spurdan, etc.

Complex/ Combined Formulas

فعلاٌ خدافظ [fe:lan xodāfez]

Meaning: “Goodbye”

بای بای ما رفتیم [bāy- bāy, mā raftim]

Meaning: “Goodbye, I’m going”.

پس میبینمت خدافظ [pas mibinamet, xodāfez]

Meaning: “See you then, goodbye”!

انشالله که [inšāllah ke] (“God willing”) + “You may always be happy/ healthy”

Form./ Inf.: انشالله که همیشه سلامت باشین [inšāllah ke hamiše salāmat bāšin]

“God willing, you may always be healthy”

Form./ Inf.: انشالله که همیشه خوش و خرم باشین [inšāllah ke hamiše xoš va xorram bāšin]

“God willing, you may always be happy”

اجازه مرخصی به بنده میفرایین؟ [Ejāze-ye moraxasi be bande mifarmāyin]

Meaning: “Would you please let me leave your presence”.

اگه اجازه بفرماییین بنده دیگه یواش یواش زحمتو کم کنم [age ejāze befarmāyin, bande dige yavāš-yavāš zahmato kam konam]

Meaning: If you allow me, my humble self will subtly lessen the trouble (of my presence).