The modern descendants of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language may be divided into a dozen branches, including Slavic, Germanic, Italic, Celtic, Greek, Armenian, etc.

One of those branches is Indo-Iranian, which can be divided into two subbranches: Indo-Aryan and Iranian. The Indo-Aryan languages are mostly spoken in the Indian subcontinent in South Asia and include languages like Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Marathi, Gujarati, etc.

On the other hand, the Iranian languages, i.e. languages descended from a single Proto-Iranian ancestor that developed from Proto-Indo-Iranian some 4000 years ago, are spoken in the Middle East, Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, etc.

The Iranian languages have a rich history and have been spoken across vast areas, from Mesopotamia to the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang, China.

Iranian languages are divided into two major groups, East and West Iranian. Among the modern languages, Persian and Kurdish belong to the western group, while Pashto and Ossetic belong to the eastern group. These groups are further divided into northern and southern subgroups. For convenience purposes we have preserved the traditional division of East Iranian into Southern and Northern branches, although this division should not be held as an absolute indicator of genetic relationship of the languages concerned. For Central Iranian, see A. Korn (2016).

The basic principle behind this division is the analysis of the different phonological, morphological, syntactical, and lexical features shared by the particular groups of languages and dialects belonging to the Iranian subbranch that reveal the genetic relationship between these languages.

Diachronically, the Iranian languages are arranged into Old, Middle, and New Iranian languages. These periods have been preserved unevenly, making it difficult to thoroughly study each of these periods.

The outline of the article

In this post, I have endeavored to make a comparatively complete list of the Iranian languages. Below, you can find the dry list of the languages (the so-called ‘contents’ of the post). After the list comes the main body of the post, in which you will be able to find each language together with a summary.

Under each language, first, the speakers and the territory over which the particular language is spoken are described. Next, information is given on the literary status and characteristics of the language and finally a short description of the grammar is provided.

At the end of this article you may find the bibliography on Iranian languages.

I hope that this will be helpful to all those interested in or making their first steps in the Iranian studies.

List of all Iranian Languages

Old Iranian Languages

1. Old Persian

Period (attested): VI-IV centuries B.C.

Region: Persis/Pārs (Fārs)

Writing system: Old Persian cuneiform.

Sources: Achaemenid inscriptions; Greek, Aramaic, Hebrew, Akkadian, Elamite loanwords.

Grammars/Manuals: Kent, R. G., Old Persian: Grammar, Texts, Lexicon; Skjærvø, P. O., Introduction to Old Persian, 2016; Schmitt, R., Avestisch, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, pp. 56-85; Skjærvø, P. O., ‘Old Iranian’, in Windfuhr, G. (ed.) The Iranian Languages, London/New York, 2009, pp. 43-195.

Text editions (and translations): Schmitt, R., Die altpersischen Inschriften der Achaimeniden, Wiesbaden, 2009; Livius.org

Dictionaries: Schmitt, R., Wörterbuch Der Altpersischen Königsinschriften, Wiesbaden, 2014.

Speakers and area. The Old Persian language was spoken by the Persian tribes (OP pārsa-) living in the historical region of Persis (< Greek Περσίς), that corresponds to the modern-day province of Fars of the Islamic Republic of Iran. It was one of the official languages of the Achaemenid Empire, along with Akkadian, Elamite and Aramaic.

Script. Old Persian is attested in Achaemenid royal inscriptions (VI-IV cc. BC.), which were inscribed on various hard surfaces, like rocks or stone/metallic objects, and, at least once, on a clay tablet (Stolper & Tavernier 2007). It is written with a peculiar cuneiform script, which was probably adopted during the reign of Darius I (522-486 BC.).

This language seems to have been spoken long before it was committed to writing in the VI century BC., and in the later inscriptions it already displays signs of grammatical and phonetic change (signifying the transition from Old Persian to Middle Persian).

Grammar. Old Persian belongs to the Southwestern group of Iranian languages. It has an inflected grammatical structure, which means that it has a complex grammar with 3 grammatical genders, 6 noun-cases (Nom. Acc., Gen.-Dat., Instr.-Abl., Loc., Voc.), 3 voices (Act., Mid., Pass.), 3 numbers (Singular, Dual, Plural), etc.

A major impediment for the study of Old Persian grammar is the very limited character and style of the Achaemenid inscriptions.

The following phonetic developments separate OP from the other Old Iranian languages of the same period:

Old Iranian (reconstructed) *ts > Old Persian θ (= th); OI *dz > OP d; OI *tsw > OP s; OI *θr > OP ç; OI *dw > OP duv/dv; etc.

2. Avestan

Period: between 1500 and 500 BC.

Region: unknown.

Writing system: Avestan alphabet (51 letters).

Sources: Avesta (the collection of the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism).

Grammars/Manuals: Skjærvø, P. O., Introduction to Old Avestan, 2006; Skjærvø, P. O., Introduction to Young Avestan, 2003; Kellens, J., Avestique, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, pp. 32-55; Sokolov, S. N., Avestiyskiy Yazik, Moscow, 1961; Martínez, J. & de Vaan, M., Introduction to Avestan, Brill, 2014.

Text editions (and translations): Geldner, K., Avesta: The Sacred Book of the Parsis, 3 vols. Stuttgart, 1886-1896; Darmesteter, J.. Le Zend-Avesta, 3 vols., Paris, 1892-1893; Wolff, F., Avesta, die heiligen Bücher der Parsen, Leipzig, 1910; Bartholomae, Chr., Die Gatha’s des Awesta: Zarathushtra’s Verspredigten, Strasburg, 1905; Insler, S., The Gāthās of Zarathustra, Tehran and Liège, 1975.

Dictionaries: Bartholomae, Ch., Altiranisches Wörterbuch, Strassburg, 1904.

Name. Avestan is the language of Zoroastrian scripture that has been preserved in various manuscripts, the oldest of which dates to 1288 AD.

Avestan is not the real name of the language. We have neither the tribal/ethnic name of the speakers, nor the name of their language. The name Avestan is adopted from the name of the sacred book of Zoroastrianism, the Avesta (previously it also used to be called Zend)

Speakers and area. Despite the late date of the preserved manuscripts, the native speakers of Avestan lived sometime between the second half of the 2nd millennium and early half of the 1st mil. BC. This approximate date has been suggested based on the close similarity of Avestan and the language of the Rig Veda on one hand, and Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenid inscriptions, on the other.

A number of regions in historical Eastern Iran (Central Asia, Afghanistan) have been proposed as the native land of its original speakers, though none of them can be accepted with absolute certainty.

Based upon the language of the Avestan texts, Avestan is divided into two dialects, Old and Young Avestan. Most of the texts in the Avesta (Yasna, Yašts, Videvdad, etc.) are written in Young Avestan, and only a portion of it is written in the Old Avestan (also called Gathic) dialect (Gathas, Yasna Haptaŋhāiti). The relation of these two dialects is debated, though the majority of scholars consider them to represent the earlier and later phases of the same language.

Script. The current Avestan script was invented somewhere between the IV or VI centuries A.D. It was based on the Pahlavi alphabet (see Middle Persian). It has 14 vowels and 37 consonants. Before the invention of the alphabet, the Avestan language was preserved by successive generations of Zoroastrian priests by means of oral tradition.

Grammar. Avestan is a highly inflected language. Its noun distinguishes three genders (masculine, feminine, neutral), three numbers (singular, dual, plural), and 8 cases (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive, instrumental, ablative, locative, vocative). Old Avestan has a more archaic character and is closely related to the dialect of the hymns of the Rig Veda.

The main phonetic developments in Avestan when compared to Old Iranian (reconstructed), are the following: Old Iranian *ts > Avestan s; OI *dz > Av. z; OI *tsw > Av. sp; OI *θr > Av. hr; OI *dw > Av. b; etc. (cf. Old Persian)

3. *Median

Period: around VIII-VI cc. BC.

Region: Media Proper

Writing system: None

Sources (secondary): Greek, Old Persian, Aramaic, Assyrian texts.

Grammars: Mayrhofer, M., Die Rekonstruktion des Medishcen, AÖAW (105), 1968, pp. 1-22;

Text editions: None

Dictionaries: None

Speakers and area. Median was the language of the Median tribes that constituted the ruling core of the Median confederacy (sometimes called “empire”), which existed between 700 and 550 BC.

The Median tribes are first mentioned in the Assyrian royal records of King Shalmaneser III (858-824). Their main area of habitation included the territories of South Atropatene and Media Proper, which constitute the north-western quarter of modern Iran.

Script. Nothing is known about the literary status of Median. Despite being the royal language of the Median state, no written monuments or records have been discovered in this language.

The main evidence for Median comes from secondary sources, like Greek, Aramaic, Assyrian, and Old Persian sources, which have preserved a number of loanwords and proper names from Median. This has helped scholars reconstruct the basic phonetic structure of this language.

Grammar. In this (phonetic) aspect Median shows remarkable similarity to the phonetic system of Avestan, having only slight phonetic differences from it. Thus Old Iranian *ś has become Median and Avestan s, while it is ϑ in Old Persian. Other such examples include: OI *ź/j > M., Av. z and OP d; OI *śṷ > M., Av. *sp and OP s, etc.

Nothing particular is known about the grammatical structure of Median, except that it was flectional, like the other Old Iranian languages.

4. *Scythian Languages

Period: mid-1st mil. BC.

Region: areas north of the Black Sea, Kazakhstan, Xinjiang (PRC)

Writing system: None.

Sources (secondary): Greek, Old Persian, Aramaic, Assyrian loanwords.

Grammars: Abaev, V. I., Skifo-sarmatskiye narečiya, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Osnovi Iranskogo Yazikaznania I, Moscow, 1979, pp. 272-364.

Word list: See Abaev 1979: 276-311

Speakers and area. Scythian or Saka was the language or rather the cluster of interrelated dialects of the Scythian tribes that inhabited the vast areas of South Russia and modern Kazakhstan in the 1st millennium B.C.

Script. Like Median, these languages have not been preserved in any written form. The only evidence for the existence of these languages, besides the existence of its descendants (like Ossetic), are a number of loanwords, toponyms, and personal names (around 200) that have been preserved in various textual sources from that time, especially in the writings of Greek authors. These words serve as a basis for the phonetic reconstruction of this dialect group.

Grammar. No means are available for the reconstruction of the grammar of these languages.

Some Middle and New Iranian languages, like Khotan Saka and Tumšukese (Middle Iranian period) and Ossetic (New Iranian period), are considered to be descendants of this language.

Middle Iranian Languages

Western Iranian Languages

5. Middle Persian (Pahlavi)

Subgroup: Southwestern

Period: 3rd c. BC - 9th c. AD

Region: Pārs (Fārs)

Writing: Pahlavi alphabet, Manichaean (Palmyrenean) alphabet

Main sources: Sasanian inscriptions, Zoroastrian Pahlavi literature, Manichaean Middle Persian literature.

Grammars/Manuals: Skjærvø, P. O., Introduction to Pahlavi, 2007; Skjærvø, P. O., ‘Middle West Iranian’, in Windfuhr, G. (ed.) The Iranian Languages, London/New York, 2009, pp. 196-278; Rastorgueva, V. S., Srednepersidskiy Yazyk, Moscow, 1966.

Text editions: Pākzād, F., Bundahišn, Zoroastrische Kosmogonie und Kosmologie, Band I, Kritische Edition, Tehran, 2005; Madan, Dh. M., The Complete Text of the Pahlavi Dinkard, vol. I & II, Bombay, 1911; Jamasp-Asana, J. M., Corpus of Pahlavi Texts, Bombey, 1913.

Dictionaries: MacKenzie, D. N., A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary, London, Oxford University Press, 1971; Nyberg, H. S., A Manual of Pahlavi, vol. II, Wiesbaden, 1974; Durkin-Meisterernst, D., Dictionary of Manichaean texts, vol. III, Part 1. Dictionary of Manichaean Middle Persian and Parthian, Brepolis, 2004.

Speakers and area. Middle Persian (MP) is the direct descendant of Old Persian and the ancestor of New Persian.

It was spoken in the Pārs region, what is now the province of Fars of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Middle Persian had a prominent role during the Persian Sasanian dynasty (224-651 AD) which came from Pārs. Middle Persian was the native tongue of the Sasanian rulers, and for this reason MP became the state language of the Sasanian Empire, which stretched from the Euphrates to modern-day Afghanistan.

Later, it spread to the northeastern regions of the Sasanian Empire (Xwarasan, Khurasan), where it replaced the native Parthian. During the Islamic period, the Persian dialect of Khurasan became the main literary standard of Persian.

Script and literature. Main documentation of MP comes from two major sources: Middle Persian Zoroastrian and Manichaean religious texts. There are also Sasanian royal inscriptions left mostly by the early Sasanian kings and high-ranking officials of the state, which, as authentic epigraphical monuments, are important (besides the obvious historical reasons) for reconstructing the history of MP.

Most of the written MP sources can be dated between the 3rd-9th centuries AD.

Middle Persian Zoroastrian literature (also called Pahlavi literature) is comparatively rich and almost completely of religious character. It is written in the Pahlavi alphabet, which is a very complicated script. It developed from the older Aramaic alphabet and has only 14 characters (despite MP having 29/31 sounds). Major written texts in Zoroastrian Middle Persian include: Bundahišn, Dēnkard, Wizīdagīhā ī Zādsparam, Ardā-Wīrāz-Nāmag, Ayādgār ī Zarērān, Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšēr ī Pābagān, etc., and translations and commentary of parts of the Avesta.

Manichaeism was a gnostic religion founded by the prophet Mani (216-274 A.D.). Manichaean preachers were active in the Roman, Sasanian empires and later also in China.

Manichaean MP literature is written in a Palmyrenean type of alphabet which has 30 letters and thus provides scholars with a clearer picture of the phonetic structure of MP. The Manichaean MP texts were discovered in Turfan in the beginning of the 20th century. Most of the texts are only fragments from various religious works. One of the original books in Manichaean MP is the Šābuhragān.

Grammar. MP has an analytical grammatical structure, which makes it closer to New Persian. It has preserved no cases, although the Early Sasanian inscriptions attest to the initial existence of two cases: direct and oblique. This can be observed in the differentiated use of the 1st singular personal pronoun an (dir.) vs. man (obl.), and the use of forms like brād, pid (dir.) vs. brādar, pidar (obl.). No traces of grammatical gender nor dual number have been preserved. Phonetic structures have been simplified, leading to the monophthongization of OI diphthongs, e.g. -ai- > ē. -au- > ō (OP raṷcah- > MP rōz; OP daiva- > MP dēw).

6. Parthian

Subgroup: Northwestern

Period: 3rd c. BC - 6/7th c. AD

Region: Parthia Proper (Khurasan)

Writing system: Parthian alphabet, Manichaean (Palmyrenean) alphabet.

Sources: Nisa documents, Manichaean Parthian literature,

Grammars/Manuals: Sundermann, W., ‘Parthisch’, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, ss. 114-137; Molčanova, E. K., ‘Parfyanskiy yazik’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yaziki, vol. I, Moscow, 1999, pp. 14-27; Reza’i-Baghbidi, H., Dastur-e zabān-e Pārti (Pahlavi-ye Aškānī), Tehran, 1381 (2002/3).

Text editions: Boyce, M., A reader in Manichaean Middle Persian and Parthian, Acta Iranica 9, 1975.

Dictionaries: Durkin-Meisterernst, D., Dictionary of Manichaean texts, vol. III, Part 1. Dictionary of Manichaean Middle Persian and Parthian, Brepolis, 2004.

Speakers and area. Parthian was originally the language of the population of Parthia proper (the Parthians), a region that was situated in the northeastern part of modern Iran (Khorasan), and southern Turkmenistan. After the rise of the Arsacid dynasty in this region and the creation of the Parthian Empire, Parthian gained importance and eventually became the official language of the state.

It appears that as it gained prominence in the political and administrative spheres, it started spreading westwards into the area of historical Jibbāl (the region between modern Iranian Kurdistan and Isfahan) and partially replaced the local Median dialects.

In the late Sasanian period, when Parthian had long lost its importance, it became replaced by Middle Persian in Xwarāsān (Khurasan) itself and soon died out.

Script and literature. The main sources for the study of the Parthian language are the Manichaean manuscripts written in Parthian (see Boyce 1960). They are written in the Manichaean (Palmyrenean) script and were discovered in the Turfan Oasis by the European archeological expeditions at the beginning of the 20th century.

The Manichaean script had around 30 letters. This has provided scholars with the conventional means to the study the phonetic structure of Parthian.

Besides these Manichaean texts, there are other sources for the study of Parthian which are of significant importance, like the 3rd c. Sasanian tri- or bilingual inscriptions, foreign loanwords (mostly in Armenian), the numerous ostraca from Nisa (near modern day Ashgabat, Turkmenistan), the Awroman parchment, etc. All these sources are written in the Parthian script, which was based on the Imperial Aramaic alphabet that was in use in the Achaemenid empire.

Grammar. Like Middle Persian, Parthian also has an analytical structure, which means it lacks gender differentiation, a case system, and it has simplified verbal inflection, etc.

In many respects, both Parthian and Middle Persian show close similarities in their grammar. During the first half of the 20th century most scholars in the field considered them to be the dialects of one language (Sundermann 1989: 106). However, its phonetic structure tells us that Parthian belongs to the Northwestern Iranian language group. Its phonetic structure is closer to that of Median and Avestan, rather than Old Persian. Cf. Old Iranian *ts > Avestan s - Parthian s; OI *dz > Av. z - Pth. z; OI *tsw > Av. sp - Pth. sp; OI *θr > Av. hr - Pth. hr; OI *dw > Av. b - Pth. b; etc. (cf. Old Persian).

Eastern Iranian Languages

7. Sogdian

Subgroup: Northeastern

Period (attested): 1st c BC - 9th c. AD

Region: Sogdiana (Soγd)

Writing system: Sogdian; Manichaean; Syriac; Sogdian-Uyghur (all alphabets); Brahmi.

Sources: Manichaean Sogdian literature; Buddhist Sogdian literature; Christian Sogdian literature; ‘Ancient Letters’ collection; Mount Mugh documents; inscriptions, graffiti, coins, minor objects, etc.

Grammars/Manuals: Gershevitch, I., Grammar of Manichaean Soghdian, Oxford, 1954; Skjærvø, P. O., An Introduction to Manichean Sogdian, 2007; Yoshida, Y., ‘Sogdian’, in Winfuhr, G., The Iranian Languages, Routledge, 2009, pp. 279-335.

Text editions: MacKenzie, D. N., The ‘Sūtra of the Causes and Effects of Actions’ in Sogdian, London, 1970.

Dictionaries: Gharib, B., Sogdian Dictionary (Sogdian-Persian-English), Farhangan, Tehran, 2004.

Speakers and area. Sogdian was spoken in the historic Sogdiana (< Gr. Σογδιανή), in the Transoxania region (Arab. Mā.warā' al-Nahr), located between the middle courses of the Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya rivers (located in modern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan). The region was connected with the name of the Sogdians already in the Achaemenid period, as it is mentioned in the Behistun inscription (6th c. B.C.) as Sug(u)da-.

The main cultural centers of the region were Samarkand and Bukhara. The inhabitants of this region were famous for their trading skills and had colonies in various centers of Central Asia, Chinese Turkestan (Xinjiang, PRC), and China (Chang’an). Their cultural and economical importance started to fade in the last quarter of the 1st millennium A.D., and soon Sogdian ceased being a spoken language.

The only surviving dialect that is related to Sogdian is spoken in the Yaghnob Valley in Northwest Tajikistan (see Yaghnobi).

Script and literature. Comparatively rich literature has survived in Sogdian, which was unknown to the scholarly community before the beginning of the 20th century.

It is written in a number of alphabets: Sogdian (< Aramaic), Manichean, and Syriac (Nestorian). Another type of alphabet is found in the inscriptions (e.g. that of Qarabalgasun) of the Uighur rulers of the Uyghur Khaganate (8th-9th cc.), which is called the ‘Sogdian-Uighur alphabet’. It is a modification of the traditional Sogdian script (< Aramaic).

There are both secular and religious literary texts preserved in Sodgian. Most of the religious literature comes from Buddhist (in Sogdian), Manichean (Manichean and Sogdian), and Christian (Syriac) communities. There is one page of a medical text preserved in Indian Brahmi script.

The majority of the surviving literature and epigraphical remains comes from Central Asia or Chinese Turkestan (Dunhuang, Turfan). Two major collections of written material of a secular character have been discovered so far, the ancient letters and the archive of Mount Mugh.

The ‘ancient letters’ are a collection of merchant letters dating back to the 4th c. AD that were discovered in Dunhuang (Xinjiang).

The ‘Mount Mugh archive’ dates back to the first quarter of the 8th c. AD. It is a collection of documents (legal and economic) belonging to the local Sogdian ruler, Dēwāštīč.

Both these collections are written in the traditional Sogdian script.

Grammar. Like most of the Eastern Iranian languages, Sogdian is a highly inflected language. One of its main characteristics is the distinction between ‘light and heavy stems’, caused by the so-called ‘Rhythmic Law’ (Sims-Williams 1989: 181-182). To put it simply, if the stem of the word is stressed, it is a heavy stem. If not, it is a light stem. The stress on the heavy stem caused the loss of final vowels, which resulted in a reduced inflectional system.

Thus, words with light stems have six cases (Nom., Acc., Gen., Loc., Abl., Voc.), while those with heavy stems have only two (direct and oblique). Three genders are distinguished: Fem., Masc., Neut. (the last one is less frequent). Three numbers, singular, plural, and dual, are attested, although the dual is rarely used and wherever it is, it has lost its function and may be called numerical (Sims-Williams 1989: 183).

8. Khotanese (Khotan Saka)

Subgroup: Northeasten

Period: ca. 600-1000 AD

Region: Khotan (Xinjiang, PRC)

Writing system: Brahmi (Central Asian)

Sources: Khotanese Buddhist literature; Khotanese documents.

Grammars/Manuals: Gertsenberg, L.G., Xotano-sakskiy yazik, Moskva, 1965; Emmerick, R. E., Saka grammatical studies, London, 1968; Emmerick, R. E., Khotanese and Tumshuqese, in Winfuhr, G., The Iranian Languages, Routledge, 2009, pp. 377-415.

Text editions: Bailey, H. W., Khotanese texts, I-V, Cambridge, 1945-1963; Bailey, H. W., Khotanese Buddhist texts, London, 1951; Emmerick, R. E., The Book of Zambasta, a Khotanese poem on Buddhism, London, 1968.

Dictionaries: Bailey, H. W., Dictionary of Khotan Saka, Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Speakers and area. The Khotanese or Khotan Saka language (Kh. hvatana-) was spoken in the territory of the historical kingdom of Khotan, which occupied the territory around the modern day Hotan (Hétián) in Xinjiang, China. Throughout its history, Khotanese was confined mostly to Khotan and its environs.

It is considered to be a Saka language. The Sakas were a nomadic Iranian people who ended up settling in different regions of Central Asia and India in the last few centuries of the 1st mil. BC and the first few centuries AD. One of their branches settled in the area of ancient Khotan and is the descendent of their language, which is known to us as Khotanese.

Script and literature. The main religion in Khotan in the second half of the 1st millennium A.D. was Buddhism. And it is mostly in the ruins of Buddhist monasteries that most of the Khotanese texts were found. The language is written in the Central Asian variety of the Brahmi script (see Emmerick 2009: 380).

The majority of the texts are of Buddhist religious character. Many are translations from Sanskrit or Prakrit Buddhist texts. Other documents, including translations of medical texts, a traveler’s diary to Kashmir, reports of information sent to the court, etc., have also been preserved (Bailey 1970: 70-72).

The majority of the documents are written either on pothi manuscripts or Chinese rolls. The first is a type of MS where the text is written on a number of rectangular paper leaves, which are then bound together by a string (which passes through a hole on the left side of the MS). The second type, as its name implies, is a roll of Chinese paper (which can reach up to 7m) on which the text was written (Emmerick 1989: 205).

Most of the texts were discovered by European expeditions in Chinese Turkestan and are in various libraries and collections in London, Paris, St. Petersburg, Munich, and Washington (for more on this literature, see Emmerick 1979). (Emmerick, R. E., A guide to the literature of Khotan, Tokyo, 1979).

Grammar. Khotanese has an analytical grammar structure like most of the Eastern Iranian languages. Its noun distinguishes two grammatical genders (masculine and feminine, not neuter) and six cases (Nom., Acc., Gen.-Dat., Inst.-Abl., Loc., Voc.), two numbers (sing. and plur., only slight traces of dual have been preserved). Nouns and adjectives are inflected according to vocalic and consonantal declensions. Verbs have two stems, for present and preterite (formed by adding -ta to the OI past participle). For further details, see Emmerick 2009: 377-415

9. Tumshuqese

Subgroup: Northeasten

Period (attested): c. 7-8 centuries AD

Region: Tumshuq (Xinjiang, PRC)

Writing system: Brahmi script (Central Asian)

Sources: partially preserved Buddhist texts; legal and economical documents, etc.

Grammars/Manuals: Emmerick, R. E., Khotanese and Tumshuqese, in Winfuhr, G., The Iranian Languages, Routledge, 2009, pp. 377-415.

Text editions: Emmerick, R. E., The Tumshuqese Karmavācanā text, Mainz, 1985.

Speakers and area. Tumshuqese is a closely related dialect of Khotanese. It was spoken in the area around what is modern Tumshuq (Ug. تومشوق), northwest of Khotan. Not much else is known about its speakers, besides that they were the descendents of the Saka tribes that settled in the area probably around the 2nd c. BC.

Script. Very few texts (around 15) have been found in this language, which makes its study somewhat problematic. A variant of the Brahmi script is employed for writing the texts. This script, despite some minor similarities to the Khotanese Brahmi, shows significant differences from the latter (esp. in writing the non-Indian consonants), which is a sign of a separate and parallel development of this script. Around two dozen pieces of documents have survived, including legal documents, Buddhist texts, sale documents, etc. (Skjærvø (1987), On the Tumshuqese Karmavācanā text, JRAS 119 (1), pp. 77-90): 77-78; Emmerick 2009: 379).

Grammar. Overall, Tumshuqese displays more archaic features compared to Khotanese. Like Khotanese, its noun distinguishes grammatical gender (masc., fem.) and has a six-case system. The lack of sufficient materials impedes the thorough study of its grammar. For further reference, see Emmerick 2009: 377-415.

10. Bactrian

Subgroup: Northeasten

Period (attested): 2nd c. A.D. - Mid-1st mil. AD

Region: Bactria (North Afghanistan, South Tajikistan and Uzbekistan)

Writing system: Greek alphabet (adopted); Manichean script (rare, one fragment)

Sources: Surkh-Kotal inscription; Rabātak inscription; Dašt-e Nāvūr inscr.; Buddhist MS fragments; Manichean MS leaf (M 1224); small epigraphical documents, coins, ostraca.

Grammars/Manuals: Livshitz, V. A., ‘Baktriyskiy yazik’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yaziki, vol. III, Moscow, 2000, cc. 38-46; Sims-Williams, N., ‘Bactrian’, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, pp. 230-235;

Text editions: Henning, W. B., The Bactrian Inscription, BSOAS 23, 1960, 47-55; Sims-Williams, N., Bactrian Documents I: Legal and Economic Documents, Oxford University Press, 2000; Gershevitch, I., The Bactrian fragment in Manichean script, Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 28, 1980, pp. 273-280.

Dictionaries: Davari, G. Dj., Baktrisch. Ein Wörterbuch, Heidelberg, 1982.

Speakers and area. The speakers of the Bactrian language (also called Tocharian, Eteotocharian) lived in the area of ancient Bactria (OP bāxtriš), a historical region around the upper course of the Amu-Darya river, now in North, North-East Afghanistan, South Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Its center, Balkh, was situated in the vicinity of modern Mazar-i Sharif (Afghanistan).

Bactrian, being the administrative language of the Kushan Empire, was also used outside Bactria.

Script and literature. Only one script is known to have been used to write Bactrian, the Greek alphabet. This alphabet was the heritage of the earlier Graeco-Bactrian kingdom and started being used in the 2nd c. AD, probably during the reign of the Kushan emperor Kanishka I (1st half of the 2nd c. AD). It had 24 letters (without Ξ (ks) and Ψ (ps); with the old letter Ϸ representing š).

Two types of writing are distinguishable: rectangular and cursive. The former is used in the earlier inscriptions (Kušan period), the latter in post-Kušan times.

Not much has survived in Bactrian. The longest written piece is the Surkh-Kotal inscription, discovered in 1957 (25 lines, c. 180 words). Other inscriptions are that of Rabātak, Dašt-e Nāvūr, etc, many of which date to the Kushan period (2nd-3rd cc. A.D.). Various small fragments of miscellaneous epigraphical documents and coins have been found (Afghanistan, South Uzbekistan, North-West Pakistan).

Recently, a number of important legal documents have been found in the territory of the former Bactrian kingdom. They have been published by N. Sims-Williams (2000).

Some manuscript fragments found in the ancient town of Loulan (Xinjiang province, PRC) testify to the existence of Buddhist Bactrian literature. One single leaf of a Manichean MS has been discovered (M 1224).

Grammar. Despite being classified as Eastern Iranian language, Bactrian shows extensive simplification in grammatical forms, like Parthian. Morphology is greatly simplified, due to the reduction of final vowels. Two cases, direct and oblique, survive. Nouns and adjectives do not distinguish grammatical gender in the inflected forms, although there is gender distinction in the use of the definite article, e.g. masc. μο and fem. μα (Livshitz 2000: 42-43). Verbal inflection shows similarities to that of West. Mid. Iranian (Sims-Williams 1989: 235). Korn (2016) has made an attempt to group Bactrian and Parthian together into one “Central Iranian” group.

11. Khwarezmian

Subgroup: North-Eastern

Period (attested): 2nd B.C.- XIV AD

Region: Khwarezm (Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan).

Writing system: Khwarezmian (< Aramaic), Arabic (secondary).

Sources: Coins, epigraphical evidence; citations in Arabic works.

Grammars: Freyman, A. A., Xorezmiyskiy yazik, vol. I, Moscow, 1951; Edelman, D. I., ‘Xorezmiyskiy yazik’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yaziki, vol. III, Moscow, 2000, cc. 95-105; Humbach, H., ‘Choresmian’, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, pp. 193-203; Durkin-Meisterernst, D., ‘Khwarezmian’, in Windfuhr, G. (ed.), The Iranian languages, Routledge, 2009, pp. 336-376.

Dictionaries: Henning, W. B., A Fragment of a Khwarezmian dictionary, London, 1971; Benzing, J., Chwaresmischer Wortindex, Wiesbaden, 1983.

Speakers and area. Khwarezmian was the ancient language of Khwarezm, a region situated on the lower course of Amu-Darya, south of the Aral sea (West Uzbekistan). The Khwarezmian language did not have much political or religious significance outside Khwarezm, which may explain the lack of documentation in this language.

Despite that, unlike other well-documented Central Asian Iranian languages, it survived for a much longer period after the Arabic conquest, at least until the 14th c. (Edelmann 2000: 95).

Script. Based on the archaeological evidence, the Aramaic script started being used to write Khwarezmian probably from the 4th-2nd cc. BC. Not much has survived besides some ancient coins, and laconic inscriptions on various types of ceramic, wooden and leather materials.

Most of the information on the phonology and grammar of this language is garnered from various fragmentary texts (words, phrases, dialogs, etc.) preserved in the works of Islamic authors writing in Arabic (see Durkin-Meisterernst 2009: 336). These texts are written in the Arabic script, with a number of added characters, like څ (c or ʒ) and ڤ (β), for representing the sounds missing in Arabic.

Grammar. The scarcity of the material doesn’t leave much room for a full reconstruction of the grammar. The nature of the script prevents researchers from reconstructing the phonetic picture of the language.

Khwarezmian has an inflected type of grammar. From the point of grammar it is more closely related to Sogdian.

Its noun distinguishes two genders, fem. and masc. (neut. was not preserved), which are expressed by means of an article. Three nominal cases are recognised in singular (direct, oblique and genitive), and two in plural (dir. and obl.). One of its main syntactic characteristics is the structure of the sentence (subject-verb-object), by which it differs from the majority of the Iranian languages.

New Iranian Languages

South-Western Group

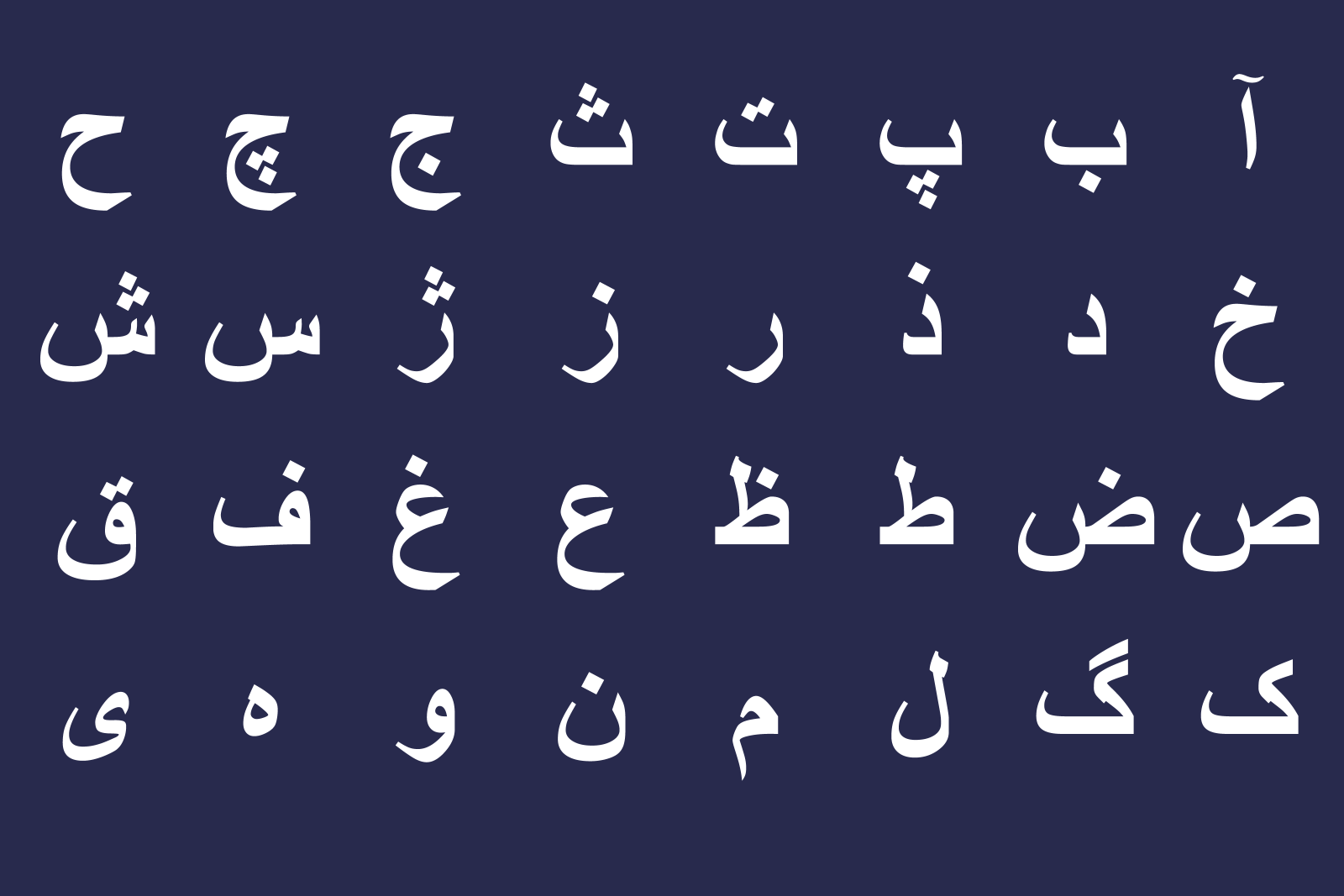

12. Persian (New Persian, Farsi)

Subgroup: South-Western

Attested since: 8/9th c. A.D.

Spoken in: Iran (IRI); Iranian diaspora (USA, Germany, Canada, Australia, etc.)

Number of speakers (native and secondary): 80 million.

Script: Arabic

Grammar descriptions/Manuals: Lambton, A. K. S., Persian Grammar, Cambridge University Press, 2003 (1st ed. 1953); Elwell-Sutton, L. P., Persian Grammar, Cambridge, 1963; Rubinchik, Yu., A., Grammatika sovremennogo persidskogo yazyka, Moscow, 2001.

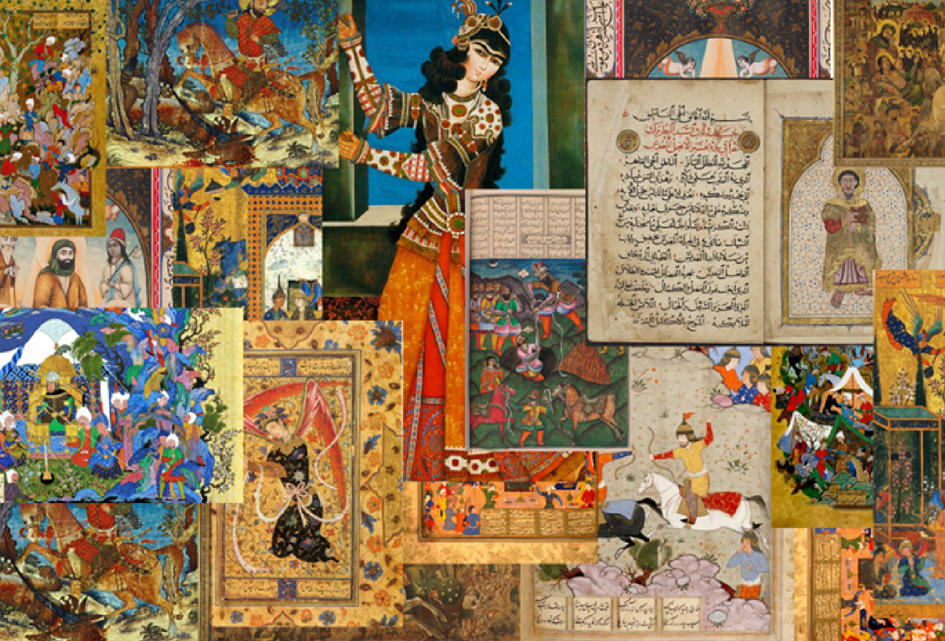

Classical literary works: Šāhnāma, Manṭiq al-Ṭair, Mathnavi-i Ma’navi, Seir ol-Moluk, Tārīx-i Baihaqī, Tārīx-i Sīstān, Laili va Majnūn, Panj Ganj (Khamsa of Nizāmī), Būstān, Gōlestān, Dīvān-i Hāfiz, etc.

Dictionaries: see below.

Speakers and area. Persian (also called Farsi) is spoken in the Islamic Republic of Iran and is recognised as the official language therein. It is spoken all over the country as a state language and language of interethnic conversation. Main areas where the lack of a local language leave Persian as the only language spoken, include: Tehran, Khorasan (Razavi, Jonubi), Semnan.The population of many major cities also employ Persian as an everyday language.

History. Despite its modern geographical position, the original home of the Persian language in general is Fārs (Pārs, Gr. Περσίς). Its history goes back to the 6th c. B.C. when the Old Persian (see Old Persian), i.e. the ancestor of the modern Persian was first attested. During the first half of the 1st millennium A.D. it was known as Middle Persian and was written in a peculiar script derived from Imperial Arameic.

The history of New Persian literary works begin to appear since the beginning of the 10th century. The language of the classical period of the Persian literature is called Classical or Early New Persian.

In the era of the Gunpowder empires (Safavid, Mughal, Ottoman) Persian became the lingua franca of the western and southern Asia. It preserved this exceptional status until the first half of the 19th century, when English in India, and Ottoman Turkish and French in the Ottoman Empire replaced it.

Literature. New Persian has an exceedingly rich literary tradition, which has been developing since the 9th century. It is unclear how and when the first literary monuments began to appear in this language. Some traditions attribute the first poem to a certain Muḥammad ibn Vaṣif, a poet in the court of the Saffarid ruler Ya’qub b. Laith. Despite the controversial nature of the evidence at hand, it seems plausible to connect the rise of the New Persian literature with the courts of the local potentates in the eastern part of Abbasid Caliphate (for details, see Lazard 1975: 606-611).

The classical period of the Persian literature lasted from the 10th to 13/14th centuries. Poets that lived in this period include: Rōdaki, Firdawsi, Farroxī Sīstānī, Manučehrī, Nāsir Khusraw, ‘Attār Neišāpuri, Omar Khayyam, Nizāmi Ganjavi, Sa’di, Hafiz, Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, etc.

In contrast to the older and more traditional Zoroastrian literature (both in Middle and New Persian), the language of Muslim Iranians integrated a significant number of Arabic loanwords (to a lesser degree in the epic Šāhnāma and more abundantly in the works of religious or scholarly nature). This development reached its climax in the mid 2nd millenium (in the Safavid, Mughal and Ottoman courts) and later was accompanied by a significant number of Turkic loanwords.

Later developments led to the creation of the modern Persian literature in the 19th c. Most of the innovations were related to the development and integration of the modern Persian language (which started being actively reformed since 1930s’), new literary genres, stylistic and thematic innovations, prominence of fictional prose writings, etc.

Prominent Persian writers of the 20th c. include: Ali Akbar Dehkhoda, Ali Dashti, Mohammad-Ali Jamalzadeh, Forugh Farrokhzad, Simin Daneshvar, Jalal Al-e Ahmad, Nima Yushij, Ahmad Shamlu, and many more.

Grammar. New Persia in a significantly analytical language, like its predessesor, Middle Persian. Major innovations (compared to MP) concern the construction of the verb structures (esp. the present forms, pr. perfect, passive voice, etc.), consonantal and semantic modifications, and lexical borrowings from Arabic (later also Turkic, French, English, etc.). Its grammar has been extensively studied and explained, see Lambton 2003, Elwell-Sutton 1963, Rubinchik 2001.

Dictionaries. In the article by Ani Beyt-Movsess you may find about Persian monolingual dictionaries (Dehkhoda, Mo’in, Amid, Sokhan, etc.). For a list of Persian-English dictionaries look a list by Mary St. Germain. For Hayyim’s (Sulayman) New Persian-English dictionary see University of Chicago’s online dictionary. For Steinglass’ Comprehensive Persian-English dictionary look here.

13. Dari

Subgroup: South-Western

Attested since: see Persian (above)

Spoken in: Afghanistan (Islamic Republic of Afghanistan)

Number of speakers (native and secondary): 27 million.

Script: Arabic

Grammar descriptions/Manuals: Glassman, E. H., Conversational Dari, Kabul, 1972 (5th ed. 2000); Entezar, E. M., Dari Grammar and Phrasebook, USA, 2010; Wahab, Sh., Beginner’s Dari, New York, 2004; Farhadi, R. & Perry, J. R., Kāboli, in Encyclopaedia Iranica, 2009.

Important literary works: see Persian (above)

Dictionaries: Nasim-Neghat, M., Dari-English dictionary, Omaha, 1992; Afγāni-nevis, ‘Abd-Allāh, Loγāt-e ‘āmiāna-ye fārsi-ye Afγānestān, Kābul, 1961.

Speakers and area. Dari is the name of the Afghan Persian literary language, based on the Kabuli dialects. It is a close relative of the Persian language in Iran, to the extent that both are considered to be different versions of the same language (along with Tajiki). Its speakers generally prefer to call their language fārsi (aka Persian). Its official name has been changed to Dari since the new constitution of 1964.

Dari is one of the two official languages of Afghanistan, together with Pashto. It is spoken in the North-western half of the country. Major dialects are spoken in Kabul, Herāt, Bādγēs, Farāh, Mazār-i Šarif, Ghor, Hazarajāt, Panjšēr, Badaxšān (see Farhadi & Perry 2009).

Almost 77 percent of the population of Afghanistan speak Dari as their first or second language.

Script and literature. The script used for Dari is the same as for Persian in Iran, i.e. Arabic. See under Persian: Script and Literature.

Grammar. The grammar of Dari is almost identical with that of Persian. There are minor differences in vocabulary, and phonology. E.g. D sarak (street) = P xiyābān, D bura (sugar) = P šekar, D māmā (uncle from mother’s side) = P dāyi, D kākā (uncle from father’s side) = P ‘amu, etc.

There are a couple of reasons for these lexical differences between Persian and Dari. First is the influence of Pashto and Hindi (e.g. puhantun ‘university’ < Pashto; čawki ‘chair’ < Hindi), which didn’t happen in case of Persian. Second is the retention of several traditional or dialectical words, in contrast to Persian. Third is the influence of the different European languages (French in case of Persian, English in case of Dari).

Overall, today with the influence of the Persian-language media (like BBC Persian), these differences are becoming less sharp.

Phonetic differences are mainly confined to the vowels, e.g. Persian final short e = Dari final short a, other short vowels like Persian e and o in Dari often correspond to i and u, i.e. the more archaic pronunciation has been preserved.

14. Tajiki

Subgroup: South-Western

Attested since: see Persian (above)

Spoken in: Tajikistan, Islamic Republic of Iran, Uzbekistan (Samarkand, Bukhara), Russia.

Number of speakers: 8 million.

Script: Cyrillic

Grammar descriptions/Manuals: Gernot, W., & Perry, J. R., ‘Persian and Tajik’, in Windfuhr, G. (ed.), The Iranian languages, Routledge, 2009, pp. 416-544; Baizoev, A., Hayward, J., A Beginner’s guide to Tajiki, London, 2004; Kerimova, A. A., ‘Tadjikskiy yazyk’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yazyki, vol. I, Moscow, 1997, pp. 96-121; Ido, Sh., Bukharan Tajik, Muenchen, 2007 (texts in Bukharan Tajik dialect); Perry, J. R., Tajik ii, ‘Tajik Persian’, in Encyclopaedia Iranica, 2009.

Important literary works: see Persian (above)

Dictionaries: Olson, R. B. & Olson, R. A., Standard Tajik-English dictionary, Dushanbe, 2000.

Speakers and area. Modern Tajiki (Tajiki Persian) is mostly spoken in the Republic of Tajikistan, and also communities have been preserved in ancient cities of Samarkand and Bukhara (Jews). The speakers of Tajiki are the descendants of the original Iranian population of Central Asia which shifted to Persian during the first centuries of the Islamic conquest.

Script. In contrast to its sister varieties, i.e. Persian of Iran and that of Afghanistan (Dari), Tajiki uses the Cyrillic alphabet for writing. The shift from the Arabic into Cyrilic system of writing (after a short period of implementation of the Latin alphabet) happened in the second quarter of the 20th century (1940).

The script has some noticeable differences from the modern alphabet of Russia. These are: ҷ (< R. ч) = j; ғ (< R. г) = γ (gh); ӽ (< R. х) = h; қ (< R. к) = q (qaf); ъ (= R. ъ) = ‘ (‘eyn, hamze).

Literature. For the classical literature of Tajiki (= Persian), see Persian. For the modern Tajiki literature, see Hitchins, K. (1991), Central Asia xv, Modern Literature, in Enc. Ir.

Grammar. Modern Tajik grammar in many aspects does not differ from that of Modern Persian. However, a number of phonetic and morphological features are setting Tajiki apart from Persian. Despite that, the both varieties are mutually well intelligible.

The consonantal systems in both Persian and Tajiki are basically the same, except that Tajiki has retained the difference between q (ق) and γ (غ), while Persian has not.

The major phonetic differences from Persian (Iran) are: Persian long ā = Tajiki o; Tajiki has retained the final short a, while in Persian it has turned into e (T. rafta = P. rafte). Besides these, the most of the long vowels in Cl. Persian (ē, ī, ū, ō) have merged with the corresponding short ones, while Persian has retained some differentiation between them (e.g. CP. šēr > P. šir, T. šir, CP. dil > P. del, T. dil). For more details on further phonetic and morphological differences between Persian and Tajiki, see Perry 2009 (Enc. Ir.).

15. Caucasian Persian and Juhuri (Tati language)

Subgroup: South-Western

Spoken in: Azerbaijan Republic; Dagestan (RF)

Number of speakers: > 37000 (by 1995) (the real number seems to be a couple of times more, see Gryunberg 1997: 141)

Script: Cyrillic

Grammar descriptions: Tonoyan, A., Kovkasyan Parskeren. Patmahamematakan usumnasirut’yun (Caucasian Persian. A Comparative-Historical survey) (Doctoral thesis), Yerevan, 2015; Grjunberg, A., Yazyk severoazerbaiydjanskikh tatov, Leningrad, 1963; Grjunberg, A., Davydova L. (1982), ‘Tatskij jazyk’, in Osnovy iranskogo jazykoznanija, Novoiranskie jazyki: zapadnaja gruppa, prikaspijskie jazyki, Moscow, pp. 231-286; Authier, G., Grammaire juhuri, ou judéo-tat, langue iranienne des Juifs du Caucase de l’est // Beiträge zur Iranistik, Band 36, Wiesbaden, Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2012.

Texts: see a sample in Tonoyan 2015: 175-196.

Name. Caucasian Persian and Juhuri are the names of two correlated south-western Iranian dialect groups spoken in modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan and Republic of Dagestan of Russian Federation. The dialects comprising Caucasian Persian are also called Southern Tati dialects and the ones comprising Juhuri (< yahudī) are called Northern Tati dialects (the use of the terms ‘Caucasian Persian’ and ‘Juhuri’ instead of Northern and Southern Tati was suggested by Artyom Tonoyan (YSU) in order to avoid confusion with the Tat (Azari) languages of Iran, see Tonoyan 2015: 9-11).

Speakers and area. Caucasian Persian (= S. Tati), is mostly spoken in the modern Republic of Azerbaijan. Here, Caucasian Persian-speaking population is generally distributed in the Apsheron peninsula and the north-eastern regions of the country (Khizi, Siazan, Shabran, Ismaili and Shamakhi regions). In Dagestan, the speakers of Juhuri (= N. Tati) are found in Derbend, Makhachkala, Buynaksk, etc.

The speakers of C. Persian are overall Muslim, while the speakers of Juhuri, as it name suggests (yahudi ‘Jewish’), are adherents of Judaism.

Northern dialects display more archaic features and have been less influenced by Azerabaijani Turkic (Grunberg 1997). Mutual intelligibility between the speakers of these dialects is difficult but not impossible (ibid.).

For a brief period in the first half of the Soviet rule there were attempts to create a literature in the Northern CP (Jewish) dialect.

Grammar. The independent development of C. Persian and Juhuri seems to have started at the early stages of the development of Early New Persian from its Middle Persian ancestor (Tonoyan 2015: 15)

The phonetic structure of the Caucasian Persian is heavily influenced by the Turkic language of the region. This is especially evident from the tendency to introduce vowel harmony (which is uncharacteristic for the Iranian languages) and the presence of vowels like ö and ü (Tonoyan 2015: 33). An interesting phonetic characteristic that sets it apart from other South-western Iranian languages, is the widely occurring rhotacism (the change of OIr. intervocalic *-t- into r). The next such characteristic is the preservation of the initial *v, which in other SW dialects has turned into b-, and the appearance of ž in the dialects of Lanhij and Shamakhi, instead of the standard ǰ/z.

From morphological characteristics that separate C. Persian from other SE dialects is the construction of the present continuous tense by using a preposition and the infinitive (Tonoyan 2015: 14-15).

Perside/Luri dialects (Bakhtiari, N. Luri, S. Luri)

16. Bakhtiari

Subgroup: South-Western

Attested since: 20th c.

Region: Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Lorestan and Khuzestan provinces (Islamic Republic of Iran)

Number of speakers: ca. > 1 million

Grammar descriptions/Manuals: Lorimer, D. L. R., The phonology of the Bakhtiari, Badakhshani, and Madaglashti dialects of Modern Persian, London, 1922; Windfuhr, G., ‘The Baktīārī dialect’, in Encyclopaedia Iranica, 1988; Anonby, E., & Asadi, A., Bakhtiari studies. Phonology, Text, Lexicon, Uppsala, 2014.

Published texts: Lorimer, D. L. R., ‘A Bakhtiari prose text’, JRAS, 1930, pp. 347-364; Anonby & Asadi 2014: pp. 96-120

Dictionaries: Anonby & Asadi 2014: pp. 157-218.

Speakers and area. The Bakhtiari language/dialect is spoken in Iran. The area occupied by the speakers of Bakhtiari is divided between the Chaharmahal va Bakhtiari province in the east (Shahr-e Kord), Lorestan (Aligudarz and Dorud) in the north, Khuzestan (Masjed-Soleyman and Haftgel) in the west and Kohgiluyeh va Boir-Ahmad in the south.

Until the second quarter of the last century, Bakhitaris were mostly occupied in seminomadic pastoralist lifestyle. The antitribal policies of the Pahlavi government resulted in a massive scale sedentarization of the population.

Grammar. Bakhtiari is a separate dialect or language closely related to the Southern Luri dialects of Boir-Ahmadi, Kohgiluyeh, and Mamasani. Together with these and the Northern Luri dialects, Bakhtiari constitutes the “Perside” southern Zagros group. This group occupies a central and transitional position between South-western dialects and Kurdish (Windfuhr 1988). Anonby (2003) calls this group (Bakhtiari together with the Northern and Southern Luri dialects) the ‘Luri language continuum’. For the map see Anonby 2003: 183.

The grammatical structure of Bakhtiari is close to that of the south-western Iranian languages, like Persian. Major differences are confined to the sphere of phonetic change, which being strong enough, has also affected some of the morphological aspects of the language (e.g. verb construction).

The most characteristic consonantal changes include: the change of intervocalic *m to w; *š > s; initial *x > h; etc. Many other characteristics are shared with other Luri dialects. For more details, see Windfuhr (1988), Kerimova (1997), Anonby & Asadi (2014).

17. Northern Luri

Subgroup: South-Western

Dialects: Giōni, Xorramābādi, Čagani, Bālā Gerivā’i

Spoken in: Lorestan, Hamadan, Khuzestan (Islamic Republic of Iran)

Number of speakers: together with Southern Luri dialects, around 3 million (not counting Bakhtiari)

Grammar descriptions: MacKinnon, C., ‘Luri language i, Luri dialects’, in Enc. Ir., 2011

Speakers and area. Northern Luri dialects are spoken in the modern Lorestan province of Iran (Khorramabad, Borujerd), South Hamadan (Nahavand) and the northern part of Khuzestan province (Andimeshk). See the map in Anonby 2003: 183.

Grammar. Grammatically, all Luri dialects resemble the standard Persian, and seem to have developed from Early New Persian (MacKinnon 2011). Major differences from modern Persian are found in the phonetic structure of the languages. For further details, see MacKinnon 2011.

18. Southern Luri dialects

Subgroup: South-Western

Dialects: Mamasani, Kohgiluyeh, Boir-Ahmadi, Rāmhormozi, Masjed-Soleymāni.

Spoken in: Kohgiluyeh va Boir-Ahmad, North Shiraz (Islamic Republic of Iran)

Script: Arabic

Grammar descriptions: MacKinnon, C., ‘Luri language i, Luri dialects’, in Enc. Ir., 2011.

Speakers and area. Southern Luri dialects are mostly spoken in the Iranian provinces Kohgiluyeh and Boir Ahmadi and Shiraz (north-west). This includes the territory between Lordegan, Yasuj, Dehdasht and Nurabad. The speakers generally belong to the Mamasani, Kohgiluyehi or Boir-Ahmadi ethnic groups.

Grammar. See Northern Luri dialects.

19. Kumzari

Subgroup: South-Western

Spoken in: Musandam (Oman), Lārak (Iran).

Number of speakers: 4000

Script: Arabic

Grammar descriptions: Thomas, B., The Kumzari Dialect of the Shihuh Tribe, Arabia, and a Vocabulary. JRAS 62 (04), 1930, 785–854; Skjærvø, P. O., Languages of Southeast Iran: Lārestāni, Kumzārī, Baškardī, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, ss. 363-369; Al Jadhami, Al Jahdhami, S., Kumzari of Oman. A Grammatical Analysis (Doctoral dissertation), University of Florida, USA, 2013; Wal Anonby, Christina van der, A grammar of Kumzari: a mixed Perso-Arabian language of Oman (Doctoral Thesis), Leiden University, Netherlands, 2015.

Texts: See Wal Anonby 2015: 262-332.

Dictionaries: See Wal Anonby 2015: 332-362.

Speakers and area. Kumzāri is a language/dialect belonging to the south-western group, and is geographically separated from the rest of the Iranian languages. The majority of its speakers live on Musandam Peninsula (on the Arabic shore of the Persian Gulf), which is part of Oman, and Lārak island (close to the Iranian shore). In Musandam, they are concentrated in two major settlements, Kumzār (کمزار) and Khasab (خصب). In Lārak there is currently one settlement, Lārak-e Shahri, where the speakers of the Lāraki dialect of Kumzāri abide.

The number of speakers of Kumzāri is estimated to be around 3000 (Anonby 2011: 29-31) in Musandam and around 1000 in Lārak (ibid.: 42-44).

No reliable information is available about the origin and history of the settlement of the speakers of Kumzāri. They consider themselves to be Arabs, and belong to the Arabic Shihuh tribe. Nonetheless, it is possible to see in the speakers of Kumzari the former inhabitants of the coastal region south of Minab on the Persian coast (the so-called Biyaban), as part of Kumzaris who interacted with A. Jayakar in the beginning of the 20th century admitted (apud Anonby 2011: 33-34). Their migration may be attributed to sometime in the 1st half of the 2nd millennium A.D.

Grammar. Due to its geographical location, Kumzari has been subject to all penetrating influence of the local Arabic Shihuh dialect. The consonantal structure of the language is mostly similar to that of modern Persian. The presence of some emphatic sounds, like ط and ص can be attributed to the influence of Arabic.

The vowels have preserved the differentiation between long (ā, ī, ē, ū, ō) and short vowels (a, i, u). The all-present glottal stop is also due to the influence of Arabic. A peculiar feature of K. is the rhotacism of the final d (e.g. dūr < dūd ‘smoke’, būr- < būd- ‘to be’, dār- < dād- ‘to give’). MP. a/u often turns into K. i (e.g. dist < dast ‘hand’, kišt- < kušt- ‘to kill’, čišt- < šust ‘to wash’, gift- < guft- ‘to say’). For more on phonetic changes, see Skjærvø 1989. For a complete survey of grammar (with texts and vocabulary), see Wal Anonby 2015.

20. Bashkardi

Subgroup: South-Western

Spoken in: Hormozgan, Kerman provinces (IRI),

Number of speakers: Unknown

Grammar descriptions: Skjærvø, P. O., Languages of Southeast Iran: Lārestāni, Kumzārī, Baškardī, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, ss. 363-369; Skjærvø, P. O., ‘Baškardi’, in Enc. Ir., 1988

Speakers and area. Baškardi (Bašākerdi) dialects are spoken in the south-eastern Iran, in the regions east of Bandar-‘Abbās, around Bašākerd, Rudbar, Minab, etc.

Bašākerd is the name of the county (Šahrestān-e Bašākerd) situated around the center Sardašt (pop. c. 3100) and the town Gouharān (formerly Angohrān, pop. 1100).

Geographically, this region is situated south of the Mārz range. However, the term Bashkardi dialects is applied to a wider variety of dialects spoken in the surrounding regions to the west, north-west and north-east of Bašākerd proper (for the description of Bašākerd, see Gershevitch 1959).

Bashkardi dialects can be divided into three clusters: 1. the dialects of Rudbār, Bandari dialect (Evazi), Hormozi, Rudāni, and Minābi; 2. North Bashkardi dialects, east and south of Mināb, including the dialects of Sardašt, Gouharān (Angohrān), Bīverč, Bešnu, Ramešk, Greon, Darza, Durkān, Gešmirān, and Mārič; 3. South Bashkardi dialects, spoken in Šahr Bāvak (the village Bābak between Sardašt and Gouharān), Garāhven, Pīrou, Pārmont, Gwāfr (= Gāfr) (Skjærvø 1988).

Grammar. Baškardi dialects are closely related to other members of the south-western group of Iranian languages, like Lārestāni or Kumzāri. The interconnection between the three groups of Bashkard dialects is not well studied. Significant differences are observable between North and South Bashkardi.

Noticeable phonetic features of these dialects are: the change of OIr. *dz > d, *θr > s, *št > st. OIr. intervocalic -t- is preserved in S. Bashkardi, and becomes r in N. Bsh. Intervocalic p > S. Bsh. p, N. Bsh. w. For further details on the phonetic and some morphological characteristics of Bashkardi dialects, see Skjærvø 1988. For the etymology and discussion of a number of Bashkardi words, see Voskanian & Boyajian 2007.

21. Fars dialects

Subgroup: South-Western

Spoken in: Fars (IRI)

Grammar descriptions: For bibliography, see Wingfuhr, G., Fars viii, Dialects, in Enc. Ir., 1999

Speakers and area: Fars dialects are mostly spoken in the Fars province of IRI. The speakers are disseminated in various settlements all over Fars province, especially the western half of the province.

Dialects. The dialects that belong to this dialect group can be divided into the following three groups (Windfuhr 1999):

1. Dialects spoken in the city of Bušehr and surroundings, counties Tangestān (center Ahram), Dašti (c. Khormuj), Daštestān (c. Borazjān).

2. Dialects of the villages spread from Kazerun to Shiraz.

3. Dialects of the villages from Ardakan to Shiraz.

4. Dialects of the villages of Daštak, Emāmzade-ye Esmā’il, Kondāzi (east of Ardakan).

5. Jewish dialects of Shiraz.

22. Larestan dialects

Subgroup: South-Western

Spoken in: South-East Fars (IRI)

Grammar descriptions: Molchanova, E. K., Larskiy yazyk, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Osnovi Iranskogo yazikoznaniya, vol. III, Moscow, 1982, pp. 364-446; Skjærvø, P. O., Languages of Southeast Iran: Lārestāni, Kumzārī, Baškardī, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, ss. 363-369.

Dictionaries: Eqtedāri, A., Farhang-e Lārestāni, Tehran, 1333/1954; Kamioka, K. & Yamada, M., Lārestāni studies 1: Lāri basic vocabulary, Tokyo, 1979.

Speakers and area. Larestani dialects are mostly spoken in the Larestan county of Fars province. Major center of the Lari population is Lar (county center). Lari is divided into a number of dialects: those of Garrāš, Evaz, Banāruye, Bastak, Saba (?) (Molchanova 1982: 364-365).

Grammar. Larestani is a distinct south-western Iranian group of dialects, which has its own characteristics different from the Fars dialects. One of such characteristics is the composition of present continuous by prefix a, instead of mī. Consonantal system is close to that of Fars dialects, Kumzari and N. Bashkardi. Some grammatical features show closeness to a number of north-western Iranian languages and dialects.

North-Western Group

23. Balochi

Subgroup: North-Western

Attested since: 19th c.

Spoken in: Iran (Sistan va Baluchestan, Hormozgan), Pakistan (Baluchestan), Afghanistan (Nimruz, Helmand), Turkmenistan (around Mary), Oman.

Number of speakers: around 10 million.

Script: Arabic

Grammar descriptions/Manuals: Elfenbein, J., ‘Balōčī’, in Schmitt, R. (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, pp. 350-362; Jahani, C. & Korn, A., ‘Balochi’, in Windfuhr, G., The Iranian languages, Routledge, 2009, pp. 634-692; Korn, A., Towards a Historical Grammar of Balochi: Studies in Balochi Historical Phonology and Vocabulary, Université de Francfort, 2003; Jahani, C., A Grammar of Modern Standard Balochi, Uppsala, 2019. See also The Balochi Language Project (different helpful materials are available).

Texts: See The Balochi Language Project.

Dictionaries: Online Baloch-English dictionary.

Speakers and area. Balochi is spoken mostly by the Baloch population (but also by some number of Brahuyis) of Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan. In Iran they are mostly concentrated in the Sīstān va Balučestān province (S-E Iran) and in the eastern part of Hormozgān. There are also some minor pockets in the Khorāsān provinces (N., R., S.) and Golestān. In Afghanistan Balochi is spoken by the population of the Nīmrūz and Hēlmand provinces in the south. In Pakistan Balochis inhabit the south-western quarter of the country, the vast areas between Quetta and Karachi (Balochistan province). In Turkmenistan there is a Balochi-speaking population in the South-East of the country (Mary). Large groups of the Balochis are found in Oman, UAE, East Africa, etc.

It is difficult to estimate the real numbers of Balochis, as it is in the case of other ethnic minorities. The latest number given by Jahani (2019: 19) is around 10 million, although the number seems to be a little bit more than that (based on the data supplied by CIA World Factbook, their number should be a little bit more than 8.3 million in Pakistan only).

Dialects. Elfenbein (1989: 359-360) gives the following division of the major Balochi dialect (6 in number):

1. Raxšānī, the most widely spoken dialect (spoken in the territory between Marv (Turkm.), Khāš (Ir.) and Kalāt (Pak.)); 2. Sarāvānī, spoken in the area between the towns Sarāvān, Irānšahr and Rāsk in Iranian Baluchestan; 3. Lāšārī, spoken in the areas around the village Lāšārī, south the town Irānšahr; 4. Kēcī, spoken in the Kēc valley in the Pakistani Makran; 5. Coastal dialects, spoken from the vicinity of Mīnāb in Hormozgan province of Iran until Karachi in Pakistan; 6. East Hill Balōčī, confined to the area north east of Quetta.

Jahani & Korn (2009: 636-638) give a simpler division into Western, Southern and Eastern dialects (see the map here).

Script and Literature. Balochi has a rich history of oral literature, which mainly offers rich specimens of epic poetry, consisting of historical, heroic or romantic ballads (Badalkhan & Jahani). However, since the late 19th century we start to find gradual penetration of written culture into Balochi cultivated circles, and the adaptation of the Perso-Arabic script for the needs of the Balochi sound system. The bulk of the literature published in Balochi is poetry, although prose is also starting to develop. Books are being published by different societies and literary academies (e.g. Balochi Academy in Quetta). Prominent writers are: Jām Durrak (18th c.), Mullā Falūl Rind, Mullā Qāsum Rind, Mast Tawkalī, Mullā Ibrāhīm, Mīr Gul Khān Nasīr, Āzāt Jamāldīnī, etc.

Grammar. Despite its geographical position, Baloch is considered to be a North-Western Iranian language, due to a number of shared isoglosses with the members of that group. Cf. Balōčī z - Parthian z - Mid. Persian d (B. zān-, Parth. zān-, MP dān-, ‘to know’), etc.

An interesting feature of Balochi is the preservation of OIr. consonants both in intervocalic and final positions (e.g. B. āp - Av. āp-; B. dantān - Av. dantan-). Among the grammatical features of Balochi that bring it close to the West. Iran. languages are the lack of grammatical gender, the dichotomy of the present and past stems, and ergative construction of the sentence in the past tense. The case-system varies among the dialects. It mainly consists of 4 cases: direct, oblique, object case, genetive (Korn 2003: 38).

24. Kurdish (Kurmanji, Sorani)

Subgroup: North-Western.

Attested since: 15th century.

Spoken in: Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Syria, Germany.

Number of speakers: around 30 million.

Script: Latin (modified), Arabic.

Grammar descriptions/Manuals: McCarus, E. N., ‘Kurdish’, in Windfuhr, G., The Iranian languages, Routledge, 2009, pp.587-633; Thackston, W. M., Sorani Kurdish: A Reference Grammar with selected reading, Thackston, W. M., Kurmanji Kurdish: A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings.

Dictionaries: Chyet, M. L., Kurdish-English Dictionary, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2003; Rizgar, B., Kurdish-English, English-Kurdish Dictionary, London, 1993; also an online dictionary of Kurdish.

Dialectical divisions. The language that is now called Kurdish, is not actually one language. It is a large cluster of correlated dialects which are divided between three main dialectical groups: Northern dialects, Central dialects and Southern dialects. It is not implausible to view them as different languages, for they are mutually unintelligible, have separate literary standards, and use different writing systems.

Speakers and area. Northern dialects (Kurmanji) are mainly spoken among the Kurdish population of the Eastern Turkish provinces (the historical Western Armenia). They are divided into North-Western (Bohtan, Diarbekir, Sinjar) and North-Eastern (most of the dialects of Eastern Turkey, Hakkari, Behdianan) subgroups (Asatrian 2009: 11). Central dialects include Sorani and Mukri, and are spoken respectively in North Iraq (Kurdistan Region) and North-West Iran (south of Lake Urmia). Southern dialects are predominantly spoken in Eastern Iraq (Khanaqin, Mandali) and Western Iran (Kermanshah, Sanandaj).

The difference between the Northern dialects on one hand and the Central and Southern dialects on the other, is so great that they are mutually unintelligible (Asatrian 2009: 12).

The number of Kurds in Turkey is estimated to be around 15 million, that of Iraq is around 6-7 million, in Iran there are ca. 5-6 million speakers and in Syria about 3-4 million (Asatrian 2009: 2-3). There are significant emigrant groups in the major urban areas of the Middle East, like Istanbul, Ankara, Tehran, Beyrouth, Baghdad etc. Many Kurds live in Germany.

Script. Today the Kurdish languages mostly employ two writing systems, based on the Latin and Arabic alphabets. The Latin script is mostly used by the Kurds living in Turkey and Syria, while the Kurds living in Iraq and Iran use the one based on the Arabic script, which is adopted for the needs of Kurdish.

Two literary dialects exist. One is based on the Kurmanji of Turkey and the other is based on the Sorani of Sulaymaniyah in Iraq.

Literature. The first attestation of Kurdish goes back to the first half of the 15th century. It is a fragment of a liturgical prayer that is being preserved in Matenadaran, Yerevan (MacKenzie 1959; Asatrian 2009: 15-16). One of the first and major literary works in Kurdish was written in the late 17th century by Ahmad Khani, and is called Mem û Zin (a love story in verse). It is considered one of the most important works in Kurdish (Kurmanji). Other works by the same author include ‘Aqidā imān (a catechism) and Nubārā Bečukān (an Arabic-Kurdish glossary). For more on classical and modern Kurdish literature, see Kreyenbroek 2005 (Kurdish written literature, in Enc. Ir.).

Grammar. While Kurmanji possesses a more archaic and authentic nature, the Central and Southern dialects have undergone considerable changes due to the overwhelming influence of south-western languages, Gurani, Luri and Persian. The noun in Kurmanji has preserved the simplified case system (direct and oblique) and gender differentiation, characteristic features of many other north-western Ir. languages. Sorani, on the other hand, completely lacks the case and gender differentiation, instead having the system of pronominal suffixes (used in forming case relations). Important grammatical feature characteristic to all branches of Kurdish is the izafe construction. For more details on the linguistic characteristics of Kurdish, see Asatrian (2009: 11-15).

25. Gorani

Subgroup: North-Western

Spoken in: Iran (Kermanshah), Iraq (Mosul)

Attested since: 18th c.

Number of speakers: unknown

Script: Arabic

Grammar descriptions: MacKenzie, Gurani, in Enc. Ir., 2002; Pireyko, L. A., ‘Gurani Yazyk’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yazyki, vol. III, Moscow, 2000, pp. 77-85.

Speakers and area. Gorani is mostly spoken in the Kermanshah province of Iran (North-West of the city of Kermanshah), in villages Gahvāra, Kandula, and in Iran, in the areas north-east of Mosul (Bajalani). Hawrāmī, a dialect of Gurani is spoken in the area west of Sanandaj (Iran).

Some Kurdish nationalist circles enlist Gorani (along with Zazaki, and other non-Kurdish languages) as a dialect of Kurdish. However, Gorani belongs to the language of the Caspean area, the speakers of which have settled in their current areas sometime in the early 2nd millennium A.D.

26. Zazaki/Dimli

Subgroup: North-Western

Spoken in: Turkey

Number of speakers: 1.5-2 million

Grammar descriptions: Paul, L., ‘Zazaki’, in Windfuhr, G. (ed.), The Iranian Languages, Routledge, 2009, pp. 545-586; Asatrian, G. S., Dimlī, in Enc. Ir., 1995.

Speakers and area. Zazaki or Dimli (as the native speakers call it) is spoken in the eastern regions of modern-day Turkey (historical Western Armenia) in the triangle between the cities of Siverek, Erzincan and Varto, and in some villages around Bitlis . There are probably some 1.5-2 million Zazas (Paul 2009: 545), who are oftentimes considered to be part of the Kurdish ethnic group.

Grammar. Linguistically, Dimli is closer to Gorani and Azari (Tati) dialects of North-West Iranian group, rather than to Kurdish (ibid.). For more, see Paul 2009.

27. Gilaki

Subgroup: North-Western

Attested since: 18th c.

Spoken in: Gilan province (Iran)

Number of speakers (native and secondary): around 3 million.

Script: Arabic

Grammar descriptions/Manuals: Stilo, D., Gilan x. Languages, in Enc. Ir., 2001/2012; Rastorgueva, V. S. et al., The Gilaki Language. English translation editing and expanded content by Ronald M. Lockwood, Uppsala, 2012; Rastorgueva, V. S, ‘Gilyanskiy Yazyk’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yazyki, vol. II, Moscow, 1999, pp. 112-125.

Texts: see Rastorgueva, V. S., et al. 2012: 225-443.

Dictionaries: Kerimova, A. A., et al., Giyansko-Russkiy slovar’, Moscow, 1980; Sotude, M., Farhang-e Gilaki, Tehran, 1953; Mar’aši, A., Vāže-nāme-ye guyeš-e Gilaki, Rašt, 1984.

Speakers and area. Gilaki is spoken by the Gilaki people, the majority of whom mostly live in the Gilan province (center Rasht) of Iran. According to Stilo (2001/2012) their number should be around 3 million.

Grammar. Gilaki is a North-Western Iranian language. Despite that it has been subject to heavy influence of Persian, which has put its mark on the phonological structure of the language. Thus, it is often possible to observe two different developments of the same Old Iranian phonemes. E.g. OIr. *tsv > *sp in NW Iranian and *s in SW Iranian; in Gilaki we have both developments: sǝbǝj ‘louse’ and sǝg ‘dog’ (the latter is a borrowing). Or, OIr. *dz > NW z and SW d; thus G. zama ‘son-in law’ (cf. NP dāmād) and dan- ‘to know’, dil ‘heart’. Among morphological borrowings from Persian it is worth mentioning the indefinite maker -i (ruz-i ‘a day’; šǝkar-i ‘a game (hunting)’) and the ezafe construction with the help of ǝ (< NP i) (Rastorgueva 1999: 114)

28. Talyshi

Subgroup: North-Western

Attested since: 20th c.

Spoken in: Gilan province (Iran); Republic of Azerbaijan

Number of speakers: less than 2 million (speculative, see Asatrian & Borjian 2005: 45)

Script: Latin, Arabic

Grammar descriptions: Miller, B. V., Talyshskiy yazyk, Moscow, 1953; Vinogradova, S. P., ‘Talyshskiy Yazyk’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yazyki, vol. II, Moscow, 1999, pp. 89-106; Hājatpur, H., Zabān-e Tālešī: Guyeš-e Xošābar, Rašt, 1383 (2004);

Texts: Miller, B. V., Talyshskiye teksty, Moscow, 1930; Lazard, G., ‘Textes en tāleši de Māsule’, in Studia Iranica 8/1, 1979, pp. 36-66

Dictionaries: Pireyko, L. A., Talyshsko-russkiy slovar’, Moscow, 1976.

Speakers and area. Talyshi or Tālišī is a North-West Iranian language closely related to the Gilaki, Mazandarani, Tati (Azari), Zaza and Gurani languages and dialects. Its speakers are mostly concentrated in the south-western part of the Caspean coastal area. The area inhabited by them is divided between Iran and Republic of Azerbaijan.

In Iran Talyshis are mostly concentrated in the north-western half of Gilan province (counties of Astara, Tāleš, Rezvānšahr, Māsāl). Many of them also live in the city of Rasht. In the Republic of Azerbaijan, Talyshis are mostly concentrated in the south-eastern part of the country (regions of Lenkoran, Astara, Lerik, Masally, Yardymly) (Voskanian 2011: 105).

Script and Literature. Unlike many other Iranian dialects that are not being used as literary languages, Talyshi has been slowly but steadily developing its own written literature since the second quarter of the 20th century. Currently two types of scripts are used for writing Talyshi: Latin, based on the Azerbaijani version of the Latin alphabet, which is used in Azerbaijan (R.) and Perso-Arabic, which is used in Iran. Major center of intellectual activity is Rasht, where periodicals and books in Talyshi are being published (on Talyshi literature, see Voskanian 2011: 105-109; on Talyshis, their language and history in general, see Asatrian & Borjian 2005).

29. Mazandarani

Subgroup: North-Western

Attested since: 10th c.

Spoken in: Mazandaran province (Iran)

Number of speakers: around 2.2 million (in 1998). Popul. of Mazandaran 3.2 million (2016).

Script: Arabic

Grammar descriptions: Rastorgueva, V. S., ‘Mazanderanskiy Yazyk’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yazyki, vol. II, Moscow, 1999, pp. 125-135.

Texts: Borjian, H., Two Mazandarani Texts from the Nineteenth Century, Studia Iranica XXXVII (2008), pp. 7-50.

Speakers and area. Mazandarani is spoken mostly by the population of Mazandaran province of IRI (along the south-eastern shores of the Caspian sea). Major population centers in the area are the cities: Sari (prov. capital), Amol, Qa’em-shahr, Chalus, etc. The vast majority of the population is concentrated in the coastal part of the province. According to Borjian (2004: 294) the large influx of immigrants from the mountainous parts of the province and the spread of the influence of Persian is limiting the sphere of influence of Mazandarani. The absolute majority of the Mazandarani-speakers is bilingual. For more on the sociolinguistic situation of Mazandarani and literature (with extensive bibliography), see Borjian (2004).

Literature. Mazandarani (old name Tabari) is one of the unique New Iranian languages that has a literature almost as old as New Persian. It goes back to the 10th century. Despite that, not many literary monuments have been preserved in Tabari. Two prominent and comparatively extensive specimens are: Maqāmāt al-Harīrī (c. 13th c.) and an interlinear translation of Qur’an (c. 17th c.) kept in the library of the Grand Lodge in Edinburgh (Borjian 2004: 293).

Grammar. Mazandarani grammar is overall similar to that of other Caspian dialects, and has been under the heavy influence of Persian. For further details, see Rastorgueva 1999.

30. Semnani

Subgroup: North-Western

Spoken in: Semnan (Iran)

Number of speakers: unknown

Grammar descriptions: Pakhalina, T. N., ‘Semnanskiy Yazyk’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yazyki, vol. II, Moscow, 1999, pp. 144-148; Pakhalina, T. N., ‘Semnanskiy Yazyk’, in Osnovy Iranskogo yazykoznaniya III, Moscow, 1991; Christensen, A., La Dialect du Sämnān, København, 1915; Morgenstierne, G., Notes on Sämnani, Norsk Tidsskrift for Spronviderskap, 1958, v. 18.

Dictionaries: Sotoodeh, M., Farhang-e semnāni-sorkhei-lāsgerdi. sangesari-shahmirzādi, Tehran, 1342/1964.

Speakers and area. Semnani is the language spoken in the city of Semnan (the center of the province of Semnan, IRI) and surroundings.

31. Sangesari

Subgroup: North-Western

Spoken in: Semnan (Iran)

Number of speakers: unknown

Grammar descriptions: Rastorgueva, V. S., ‘Sangesari yazyk/dialekt’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yazyki, vol. II, Moscow, 1999, pp. 166-174.

Dictionaries: Windfuhr, G., & Azami, C. A., A dictionary of Sangesari with a grammatical outline, Tehran, 1972; Sotoodeh, M., Farhang-e semnāni-sorkhei-lāsgerdi. sangesari-shahmirzādi, Tehran, 1342/1964.

Speakers and area. Sangesar is a separate language spoken in the village of Sangesar in the Semnan province. Despite being sometimes classified as a member of the Semnani dialects, its difference with the latter is so significant that it is necessary to classify Sangesari as a distinct language.

32. Sivandi

Subgroup: North-Western

Spoken in: Fars province (Iran)

Number of speakers: unknown

Grammar descriptions: Molchanova, E. K., ‘Sivendi yazyk/dialekt’, in Rastorgueva, V. S. (ed.), Iranskiye yazyki, vol. II, Moscow, 1999, pp. 236-245.

Speakers and area. Sivandi is a North-Western Iranian language spoken in a South-Western Iranian area. Its speakers live in the village of Sivand, north of Shiraz (Fars province).

33. Tati/Azari dialects

Subgroup: North-Western

Spoken in: Qazvin (Takestan), Ardabil (Khalkhal), East Azarbaijan (Karingan, Harzand) (IRI)

Number of speakers: unknown

Grammar descriptions: Yarshater, E., A Grammar of Southern Tati Dialects. Median Dialect Studies I, Hague-Paris, 1969; Yarshater, E., The Tati dialect of Tarom, in Henning Memorial Volume, pp. 451-467.