There are thousands of languages spoken on Earth today. Each of these languages is an essential part of the identity of its speakers.

Thus, it should not be surprising that sometimes the name of a language can become a contentious issue.

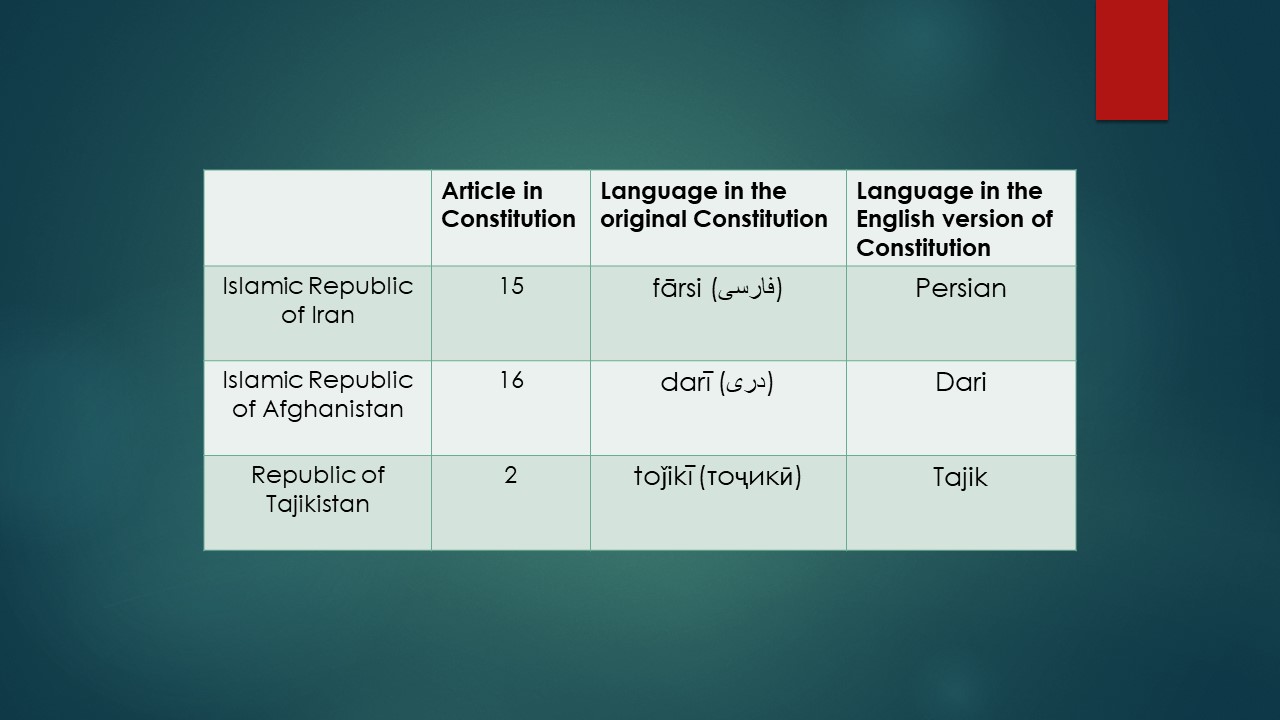

In the three countries in which Persian is the official language - Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan - it has a different name: Persian/Farsi (Iran), Dari (Afghanistan) and Tajiki (Tajikistan).

Why do we have such confusion, and which name is more correct to use for the language of Iran: Persian or Farsi?

Here, I am going to approach the question from different angles. I hope this will help you clarify this issue.

The legal approach

“What is the official language of such and such country?” is a very important question in the modern world. Each country conducts its official business in a particular language, which is intelligible to every citizen of that country (at least in theory).

Imagine the chaos that would ensue, if everyone suddenly decided to only speak their own language in Great Britain, instead of English! Pakistani lawyers would write contracts in Urdu, Chinese professors would suddenly start lecturing in Chinese, and Indian manufacturers would write their instructions in Hindu or Gujarati!

But this doesn’t happen, because there is one standard language, English, recognized by everyone as the language of communication (with the exception of Wales, where Welsh is also an official language).

This is why, as a general rule, countries define their official languages in their constitutions (ironically enough, English is not de jure recognized as the official language of the UK, nor England).

Thus, the above-mentioned Persian-speaking countries define their official state language in their constitutions.

Let’s compare the official names of those languages and their English translations.

Observe that while Afghanistan and Tajikistan call their language “Dari” and “Tajiki” in the English versions of their constitution, the English version of Iranian constitution calls the language “Persian”. This means that they officially consider “Persian” to be the English translation of “fārsi”.

The Academy of Persian Language and Literature

In 1935, an institution called “The Academy of Iran” (Farhangestān-e Irān) was established by the government of Iran. This institution was responsible for carrying out language reforms, modernizing the language and solving other issues related to Persian.

In 1990, the opening of the Third Academy (called “The Academy of Persian Language and Literature” - APLL) was officially announced.

This academic body carries official weight on matters related to the Persian language. Hundreds of respected scholars are members of this institution.

In 1993, it released an official statement (p. 152), in which it recommended strongly against the use of “fārsi” as opposed to “Persian”.

Of course, this statement was directed more against the usage of this name in the official correspondence of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the IRI. However, we can still garner the official stance of such an authoritative body as the APLL concerning this particular issue.

The academic approach

It is much more advisable to refer to linguists about these sorts of issues. So, which name do linguists use themselves?

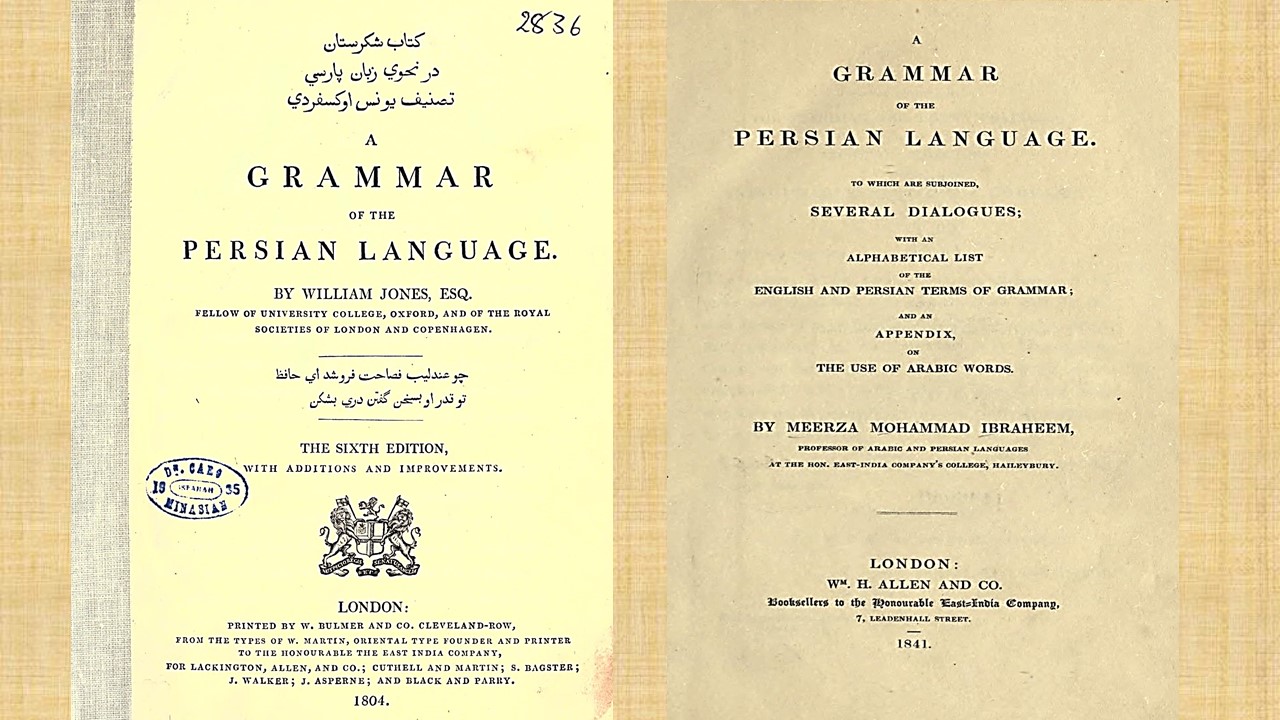

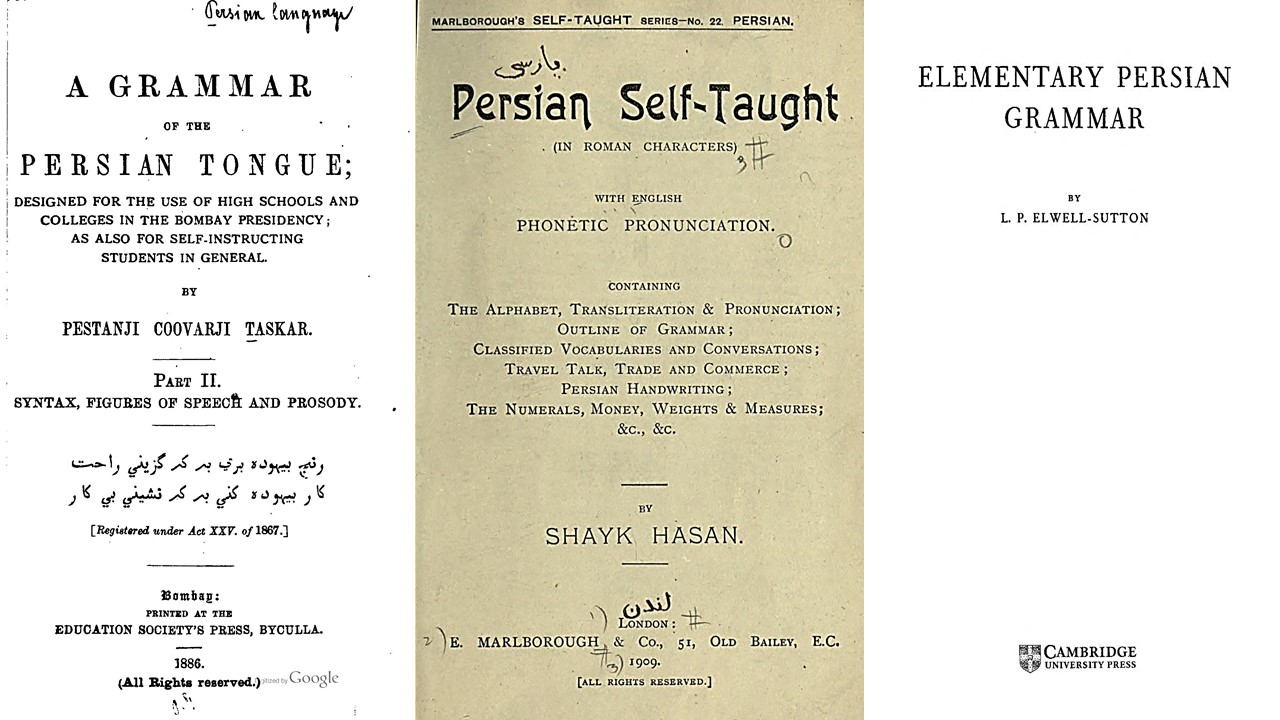

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, along with the rise of interest in Persian literature, a number of Persian textbooks and grammar books were published. All of them referred to the language as “Persian”, despite the fact that even then the language was called “fārsi” by the majority of its native speakers. Here are the title pages of some of those textbooks:

|  |

Modern specialists in Iranian studies overall prefer “Persian” over “Farsi”. Thus, for instance, Gernot Windfuhr, a distinguished authority on the Persian language, calls the language of modern-day Iran “Modern Standard Persian” or simply “Persian” (see Windfuhr, G. L., “Persian and Tajiki”, in Windfuhr, G. (ed.), The Iranian Languages, 2009, London/New York, pp. 416-544).

This is only one case among many. The absolute majority of scholars and textbooks (G. Lazard, L. Paul, E. Yarshater etc.) use “Persian”, while only very rarely, if ever, you will come across a specialist in Iranian Studies, who prefers the term “Farsi” over “Persian” in an academic publication.

The historical approach

Abdullah Ibn Muqaffa was a Persian scholar and translator who lived in the 8th c. AD. All of his works have disappeared since then.

However, many excerpts from his books survive until today. In one of these, he speaks on the languages spoken in Iran (preserved in Ibn al-Nadim’s Al-Fihrist).

According to him, at his time there were five major ‘dialects’ of Persian: al-Fahlawiya, al-Dariya, al-Fārsiya, al-Xūziya and al-Sūryāniya.

From this list we can leave out the last two languages. Xūziya was the language of modern Khuzistan, probably the successor of ancient Elamite. So, it wasn’t an Iranian dialect. This is also the case with Sūryāniya, which is Syriac (a Semitic language spoken up until today).

Now, back to the first three. Among these, Fahlawiya, or Pahlavi, was the language of the north-western quarter of modern-day Iran (spoken in Isfahan, Ray, Hamadān, Māh-Nihāwand and Āzarbāijān).

Fārsiya or Pārsi was the language of the Zoroastrian priests and scholars and the people of Fars. This is the same language we find today in Middle Persian Zoroastrian literature.

Well what about al-Dariya or Dari?

According to Ibn Muqaffa, Dari was the language of the city-dwellers and the royal court, which in Sasanian times resided in Mesopotamia.

It was also spoken in Khurasan and the eastern regions of the Empire. In fact, “darī” itself is an adjective that means “[the language] of the court”. It was also called “pārsi-i darī”, i.e. “court Persian”.

Dari and Pārsi were two versions of the same language. Dari was the court dialect, which gradually spread to the eastern regions of the Empire, while Parsi was the southern dialect.

The speakers of both could understand each other. Later Dari Persian also spread to the southern regions and became the standard literary language.

Persian, Dari, Tajiki.

Today, Persian is spoken in three countries: Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan. In each country it has a different name: Persian (Farsi) in Iran, Dari in Afghanistan and Tajiki in Tajikistan.

To someone who is not familiar with Persian, it might seem that these are three different languages. However, this is not entirely the case.

There are indeed slight lexical and phonetic (and small grammatical) differences between all three “languages”. Still, it would make more sense to consider them different regional variants of the same Persian language. This is why Dari and Tajiki are sometimes called Afghan Persian and Tajiki Persian. They are mutually intelligible.

So, why do we use three different names for three regional varieties of one language?

The answer to this question lies in national politics.

In the beginning of the 20th century, all speakers of Persian (in Persia, Afghanistan and Central Asia) called their language “fārsi”. In the 1920's, during the formative phase of the Tajik SSR, the policies were mostly aimed at the formation of a separate nation. This nation needed to have its own language, alphabet and literature. Thus, the term “tajiki” began to be widely used for the language of the Persian-speaking population of Central Asia.

Such is the case with Dari. Before the 1964 constitution, Afghan Persian (spoken mostly in the western and northern parts of the country) was called [Afghan] Persian (fārsi). After the new constitution was accepted in 1964, the language was officially renamed “Dari”, after the older name of the Classical Period Persian.

It is exactly after this (1960’s and 70’s) that we can see the rise of the term “Farsi” in English-language environment for the official language of Iran. Among other reasons, it seems likely that this was done in order to avoid confusion between the Persian of Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

However, I think there is no need for that. If the languages of the latter two countries are already called Dari and Tajiki, no confusion will ever arise if we’ll continue to use “Persian” for the Persian of Iran.

So which is the better name to use?

As you may have noticed in the discussion above, Iran recognizes “Persian” as the equivalent for the name of its official language.

In academic circles, the language of Iran is called Modern Standard Persian or simply Persian.

For the last few centuries, Persians have called their language “fārsi”. Despite this, when linguists and masters of Persian wrote Persian textbooks in English, no one called the language “fārsi” instead of Persian. Why should we?

This is why I think using “fārsi” for Persian is a mere redundancy.

Let me give you the example of my native language, Armenian.

Today, the language I speak as a native is internationally called “Armenian”. Well, this is not so in Armenian itself. We call our language, “hayerēn”.

Suppose someone is uncomfortable with the name “Armenian” and wants to call it “Hayeren” in English. What do you think, should this “willy-nilly” act be accepted and promoted by others? If people have called the Armenian language “Armenian” for millennia, would the change of this traditional name be of any use to anybody?

This is why I recommend using the traditional name, instead of jamming the language with different names that, in the end, refer to the same thing.

However, whichever name you prefer to use, mind that you use it in “good thoughts, good words and good actions”, as the Zoroastrians would say.